tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

Civilization

•

Jan 6, 2026

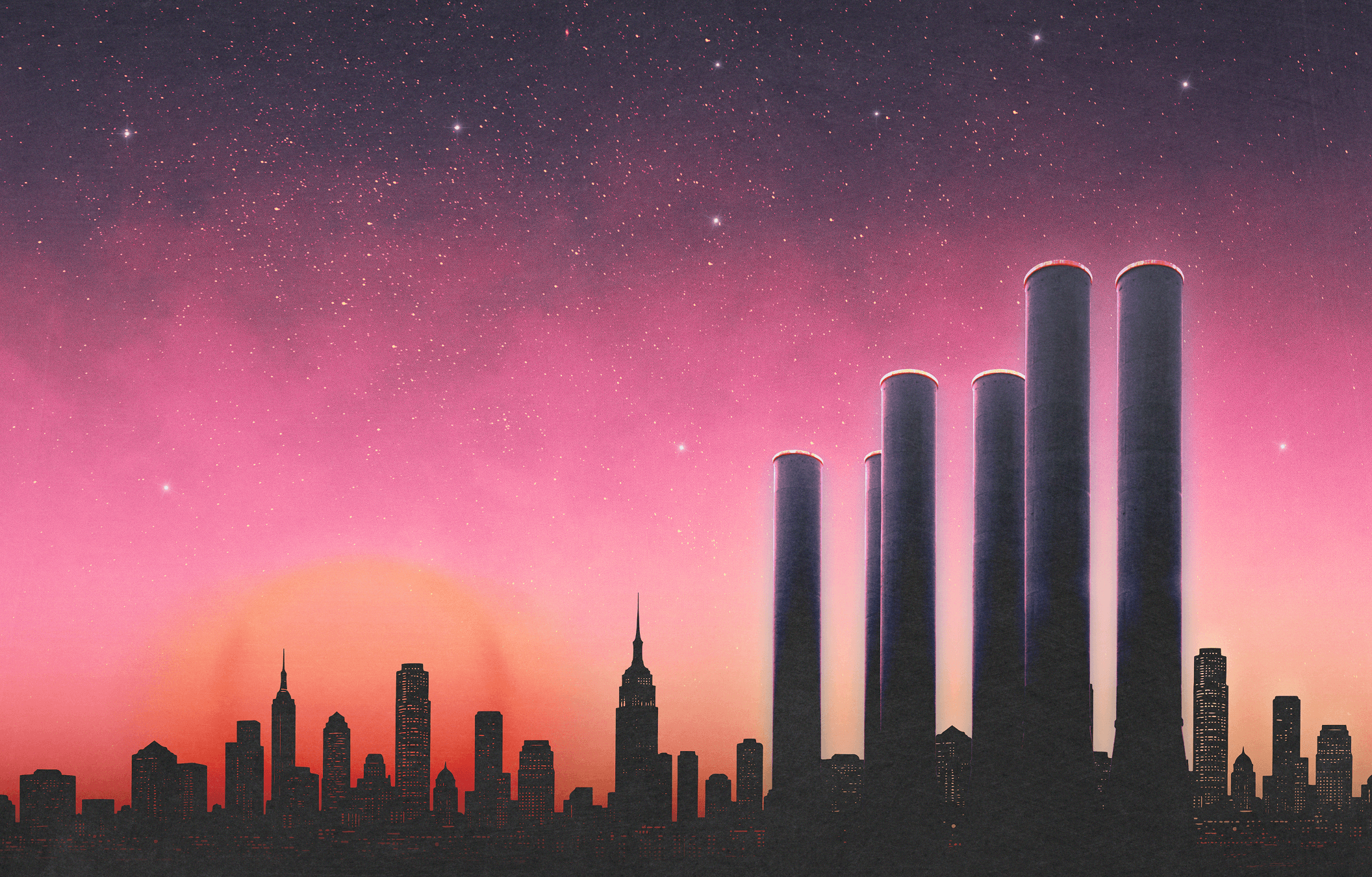

The Street and the Forge

Why American Industry Needs American Banks

Free email newsletter:

Get Arena Magazine in your inbox.

Wall Street has become a bogeyman in discussions about industrialization and industrial policy. The argument typically goes like this: financialization, the expanding if not encroaching influence of banks and investors on American life, is responsible for American deindustrialization, and an inhibitor to reindustrialization.

The Great Recession greatly tarnished the reputations of the largest banks, and they haven’t recovered. Only 17% of Americans trust Wall Street. 73% think that it needs stricter regulations. But if finance ostensibly killed America’s industry in the past, now they might be the best card we have.

This mistrust has convinced some — both on the left and increasingly the right — that America’s financial sector is an inhibitor to an industrial renaissance. Actually, it may be our nation’s secret weapon.

As a willing backer of industry, Wall Street played an essential role in America's industrialization and cemented U.S. global power in the 20th century. But since the 1990s, that same financial sector has appeared detrimental to American industry. Corporations returned 90-95% of profits to shareholders for three decades, leaving little to build or invest with.

The competition with China and a superficial understanding of China’s industrialization process and off-shoring are indeed feeding the frame of financialized capitalism versus the industrialized economy. Recently, a summary of Peking University professor Lu Feng’s ideas translated into English — that China’s industrial socialism will defeat America’s financialized capitalism — generated quite a fuss in industrial policy circles.

Lu argues that China must expand, not restrict, its manufacturing base because a large, complete industrial system (like the one China sports) is the foundation for technological innovation, economic growth, and geopolitical power. He frames the U.S. China competition as a clash between industrial socialism, with state-directed finance serving production capacity, versus financial capitalism, where Wall Street has hollowed out American industry. Lu summarizes his argument by writing, "The past 500 years of world history show that an industrial power has never lost when challenged by a financial power, even when the financial power is also a global hegemon."

The reality of this statement is plainly false. Lu doesn't give any historical examples because there are none. One could imply he's referring to Great Britain’s transfer of power to the United States in the aftermath of World War II, often compared to a potentially similar peaceful transition between the U.S. and China throughout the 2010s. But Britain was an industrial power when it peaked, and by the time the U.S. surpassed it, America had already overtaken Britain in both industrial output and financial muscle. Not to mention, the United States did not challenge the United Kingdom but, along with the USSR, aided it in its war against Nazi Germany.

Nevertheless, Lu's thesis has struck a nerve because it captures something real and worrying about America's economic trajectory since the 1990s. There is real truth in blaming financialization for aspects of American deindustrialization; short-term incentives, quarterly earnings pressure, the relentless focus on shareholder returns over long-term capital investment have offshored millions of manufacturing jobs.

The central error in Lu’s prediction is that there hasn't been any modern great power that wasn't simultaneously a financial power and an industrial power – China included. The two have never existed separately at the apex of global competition. And this is why it would be a mistake to think that, despite recent tensions between the financial sector and American manufacturing, America would be better off without it and overlook what it could do for American reindustrialization. Wall Street will be the trump card that America has to recover its industrial might.

War, Finance, and the Industrial Revolution

Finance is a technology that enables society's risk takers to take risks. And to become a great power you need people willing to gamble everything to chase an opportunity. Through history, sea men have been the risk takers.

In Medieval Europe, insurance and banking were created to cover for the risky ventures of Mediterranean merchants. The word "bank" in English, comes from the Italian (and, further up the etymology tree, Proto-Germanic)- banco, meaning "bench", referring to a physical merchant’s table where they conducted business. When a banker didn't have funds, his bench would be publicly broken, hence bankruptcy — banca rotta. As Nassim Taleb joyfully recalls whenever given the opportunity, in my native Catalonia, bankers would forfeit their heads along with their benches. The business of hedging risk, indeed.

From the Renaissance Mediterranean trade cities, financial technologies migrated to the Northern Seas, maturing into modern capitalism through fierce competition between London and Amsterdam during the Age of Discovery.

England's rise to naval and industrial dominance was inseparable from its financial innovations: the creation of the Bank of England in 1694, the development of government bonds to finance naval warfare, the rise of chartered companies like the East India Company — which was the first joint stock limited liability company — and the sophisticated credit instruments that emerged from maritime trade. These were the institutional foundations of industrialization.

Naval workshops and shipyards were the early precedent of the industrial revolution in England. This is the recipe of the triad of great power: military might, industry, and financial power, each reinforcing the others. The industrial revolution in textiles, iron, and steam was possible because of the capital mobilization systems that preceded and accompanied it.

On the other side of the Atlantic, New Amsterdam (eventually New York), the scion of the English and the Dutch, became the most sophisticated financial capital of the world. That it arose out of a Dutch-English culture is no coincidence, and that it rose to the throne of financial power during the two most destructive wars recorded in human history isn't either.

First, Wall Street would be key to channeling domestic and European investment into the U.S. for railroads, canals, and industrial expansion in the mid 1800s. Wars are expensive. You need bankers to win them, and you need them good and with deep pockets. Thankfully, America had bankers aplenty. When the horns of war resonated through the Old Continent, it was as much Wall Street's might as America’s industrial strength that helped the U.S. become the dominant power in Europe during the early 20th century. Before and during the First World War, Wall Street investment banks, notably J.P. Morgan & Co., became the main lenders and arms financiers for Britain and France, underwriting billions of dollars in war bonds and arranging purchases of food, munitions, and raw materials.

The creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913 and the New York Fed's international role gave Washington a new monetary power to match the reach of American creditors. By 1917, U.S. financial institutions had displaced European rivals in underwriting and dollar clearing. The dollar itself began to rival the pound sterling as a reserve and trade currency.

America’s direct involvement in World War I, in part to protect its investments in Europe, determined the outcome of the conflict. But it was the preceding four years of credit and supplies that made the Allies dependent on U.S. capital and tied postwar Europe to New York. After the armistice, U.S. banks financed reconstruction loans, reparations cycles, and German stabilization through the 1924 Dawes and 1929 Young Plans, embedding the U.S. in the European economic system.

This financial muscle enabled a degree of American influence well beyond the nation’s modest standing army. Loans also allowed for new markets for American manufactured goods that at the same time, would feed America’s industries. By requiring convertibility of European currencies into the dollar, the interwar dollar credit system let Washington shape European recovery and limit rival powers without a formal empire.

This paved the way for the American Western hegemony after World War II and the creation of the Bretton Woods system that granted America the condition of global super power. American industries and American boots couldn’t have taken over the world without the strength of American banks, and what was effectively the largest line of credit ever conceived.

Is Financialization to blame for Deindustrialization?

Nevertheless the prevalent narrative tells that the happy triangle between manufacturing, finance and American power collapsed in the 1980s when financialization took hold of the U.S. and promoted massive offshoring of American factories that brought us to the situation we are facing today.

The truth is that offshoring began way before the globalization of the 1980s to Puerto Rico, Mexico, and East Asia (though then, to a lesser degree). U.S. multinational corporations began shifting labor-intensive production abroad, particularly in apparel and electronics assembly as early as the 1960s. For example, the maquiladora system — foreign owned factories in Mexico that export their goods — began in 1965, when the Mexican government launched the Border Industrialization Program (Programa de Industrialización Fronteriza). Global shipping became cheaper. The first standardized shipping containers in 1956 made global supply chains economically viable in ways they had never been before.

As is today, cutting labor costs was the main driver of 20th century offshoring as the wage gap between U.S. labor and foreign workers was already significant. The proliferation of U.S. tariff exemptions also created incentives for companies to look abroad. And this was not yet the era of "Wall Street hegemony" in the modern sense, because the Bretton Woods system still constrained capital flows.

In 1971-73, Nixon ended gold convertibility, capital controls loosened, and the dollar’s value floated freely against other national currencies. The 1970s oil shocks and inflation pushed firms to seek aggressive cost cutting. Besides, better telecommunications, and just-in-time manufacturing methods made coordinating distant suppliers easier than ever.

American regulatory frameworks and the influence of powerful unions drove up costs in the steel and auto industry, making the country less competitive vis-a-vis the emerging Asian Tigers, with Japan as the main industrial threat of the 1980s.

This is when Wall Street became central. Starting in the mid-1980s, a new, radical idea took hold: companies exist to maximize immediate shareholder returns. Financial markets began pushing hard for cost cuts through leveraged buyouts. Offshoring accelerated because Wall Street rewarded companies that improved their profit margins and punished those that spent money on long-term investments in factories and equipment, investments that would not immediately increase shareholder value.

By the 1990s and 2000s, big investors rewarded companies that outsourced and offshored because it boosted quarterly profits. The playbook in running companies was that of stock buybacks, private equity takeovers, and cost cutting. Wall Street's highly globalized institutional investors rewarded this model relentlessly, and there is no point in concealing this truth. But Wall Street did not create offshoring, and to a certain extent was just amplifying and accelerating a trend that had broader ideological backing at the time.

It is not that the U.S. government wasn't supporting policies that would promote offshoring while greedy financiers went rogue. The creation of the World Trade Organization in 1995, and multiple free trade agreements like NAFTA, signed in 1992, created predictable frameworks that made offshoring the obvious move. Some might say the government was captured by Wall Street interests, but the reality is more complex. The 1990s political consensus assumed secure supply chains and that America's role as the architect of global trade was itself a form of hegemony. And that was true, at least until China’s accession to the WTO in 2001.

The end of the Cold War and the unipolar U.S.-led new world order brought a belief in frictionless global trade, where the U.S would keep the tasks at the higher segments of the value chain like design and services in the country, and outsource the lower ends. Without any serious rival, the U.S military role had become one of global policeman. According to the dominant geopolitical thought, it didn't make any sense to preserve an inefficient domestic industrial base because major great power wars “were a thing of the past.” The entire American elite consensus the three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall embraced this vision.

Wall Street followed and amplified these political choices. The interaction between these drivers matters. Wall Street's shareholder-value revolution turned offshoring from a cost-saving tactic into a dominant corporate strategy. But this happened because labor dynamics made low-skill U.S. manufacturing expensive, technology made global supply chains possible, and the political mindset of the 1990s made it all seem not just profitable but strategically wise.

When the responses to the Financial Crisis of 2007, focused on protecting America’s banking system -- while China emitted a $600 billion stimulus to keep intact its industrial base -- there had already been a decades long political consensus that excelling in manufacturing wasn’t what the US was interested in. Of course that was precisely the turning point of a rebalancing of geopolitical power that would eventually destroy such consensus.

The Strategic Imperative

The fact that China has worked to increase its financial leverage and weaken dollar supremacy should be a warning that U.S. financial power is a tool that shouldn't be discarded. China knows this. Beijing's efforts to sanction-proof its economy, develop yuan-based trade systems, and recent signals to build Hong Kong as a crypto hub despite distrust of decentralized finance all show that the Chinese Communist Party sees the importance of keeping up with financial developments. That the PRC is tentatively exploring venturing into crypto, is indeed a proof of how much Beijing could be willing to risk to counter the U.S. leadership in global finances.

America's financial hegemony is sometimes a double-edged sword. Everyone having their money in American assets creates dependencies but also vulnerabilities to foreign influence. Yet it remains a source of enormous geopolitical influence. China has become Saudi Arabia’s top oil buyer, but a large part of the Kingdom’s oil revenues will be reinvested in American assets, not Chinese.

The European counter example opposes the binary contradiction between financialization and industrialization. Europe is a hard example for those who argue that once financial capitalism takes hold, industry inevitably collapses. It is true that Europe hasn’t reached the same levels of financialization as the U.S., but many large European firms are publicly traded and must answer to financial markets, yet they remained, until recently, world leaders in the automotive industry, machinery, aerospace, and chemicals.

But Europe also shows you can deindustrialize without Wall Street-style shareholder primacy. Despite lower financialization than the US, manufacturing as a share of GDP and employment has fallen steadily since the 1980s. EU policy and regulation created strict environmental rules, high energy costs, and fragmented capital markets that made local investment unattractive. The introduction of the Euro starting in the 2000s removed national currency devaluation tools. Europe was dependent on exports to the Chinese market, but was later on outcompeted by Chinese brands in a blow to the German automotive industry.

What is worse, Europe doesn’t have the innovation and risk-taking culture that American capital markets and the venture capital ecosystem have promoted. Finance was created as a risk-enabling technology. In Europe, lack of competitiveness and regulatory frameworks, not financialization, seems to be the root in any process of de-industrialization, and might need to have more focus of attention in redressing them than financialization to promote re-industrialization.

What Reindustrialization Requires

In China the financial sector is subordinated to state-holders instead of stake-holders. That doesn’t mean that in the West, finance is detached from political incentives.

ESG is a clear example of an ideologically driven investment strategy. The fact that several major U.S. banks and asset managers pulled back from high-profile ESG commitments and some ESG-branded strategies after President Donald Trump’s return to the White House shows how Wall Street often follows instead of marking the political tone.

Reversing offshoring is more complicated because offshoring is much more economically savvy than ESG. However, rebalancing the current situation is possible. Indeed, with regard to China, we already saw American investors begin reducing their presence there around 2016, as tensions between the U.S. and China began to grow.

In the second Trump administration we have seen attempts to send clear signals about the need to put investment at the service of re-industrialization. The American Dynamism Summit in March 2025, hosted by Andreessen Horowitz, is a good example of where U.S. industry and capital might be heading. Vice President J.D. Vance's keynote speech set a clear priority of where investment should be directed to strengthen American power, in marrying automation with reindustrialization.

Later in October 2025 the J.P. Morgan & Co, announced a $1.5 trillion fund for critical industries, supporting projects that boost American power in supply chains, advanced manufacturing, defense, aerospace, energy, and frontier technologies. The truth is that if there is political clarity, the great American banks will step in to lend their muscle to finance American national projects.

Reindustrializing is not the same as industrializing. A highly financialized economy that wants to increase its industrial capacity is unprecedented. None has yet done so successfully, so we do not know if traditional industrial policy recipes will work. But we know that money is always helpful, and that's something that America’s finance knows how to make as none else in the world does. That is an advantage that shouldn’t be disregarded.

Access to capital is key for reindustrialization: credit, debt and equity capital, liquidity, and R&D investment. But it must be intelligently allocated. Financialization is bad for the real economy when speculation crowds out useful investment and rewards rent-seeking behavior. There can be policies to incentivize reinvesting state tax revenues into manufacturing via R&D tax credits, providing purchase order and capital equipment financing to derisk starting new businesses, and creating incentive structures that reward long-term domestic production.

The solution isn't to allow resentment against Wall Street to lead to dismantling American financial power. It's to redirect it. America's capital market ecosystem with good incentives could be America's secret weapon to reindustrialize instead of its enemy. A pro-industrialization framework, whether through tax policy, regulatory changes, or even a reconfigured ESG style ranking that rewards domestic production and long-term investment, could redirect Wall Street's power toward national priorities.

The dichotomy between finance or industry is an argumentative trap. The question is how to make them work together again, as they did when America rose to dominance. You need bankers to win wars. You need factories to fight them. Any strategy for American power that ignores either half of this equation has already lost.

About the Author

Miquel Vila is a geopolitical risk strategist and a non-resident fellow at the Orion Policy Institute. He can be found on X at: @MiquelVilam.