tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

Technology

•

Jan 12, 2026

Taking the Highway in the Sky

Talking America’s aerospace future with Archer Aviation CEO Adam Goldstein

Free email newsletter:

Get Arena Magazine in your inbox.

An Olympic Takeoff That Wasn’t

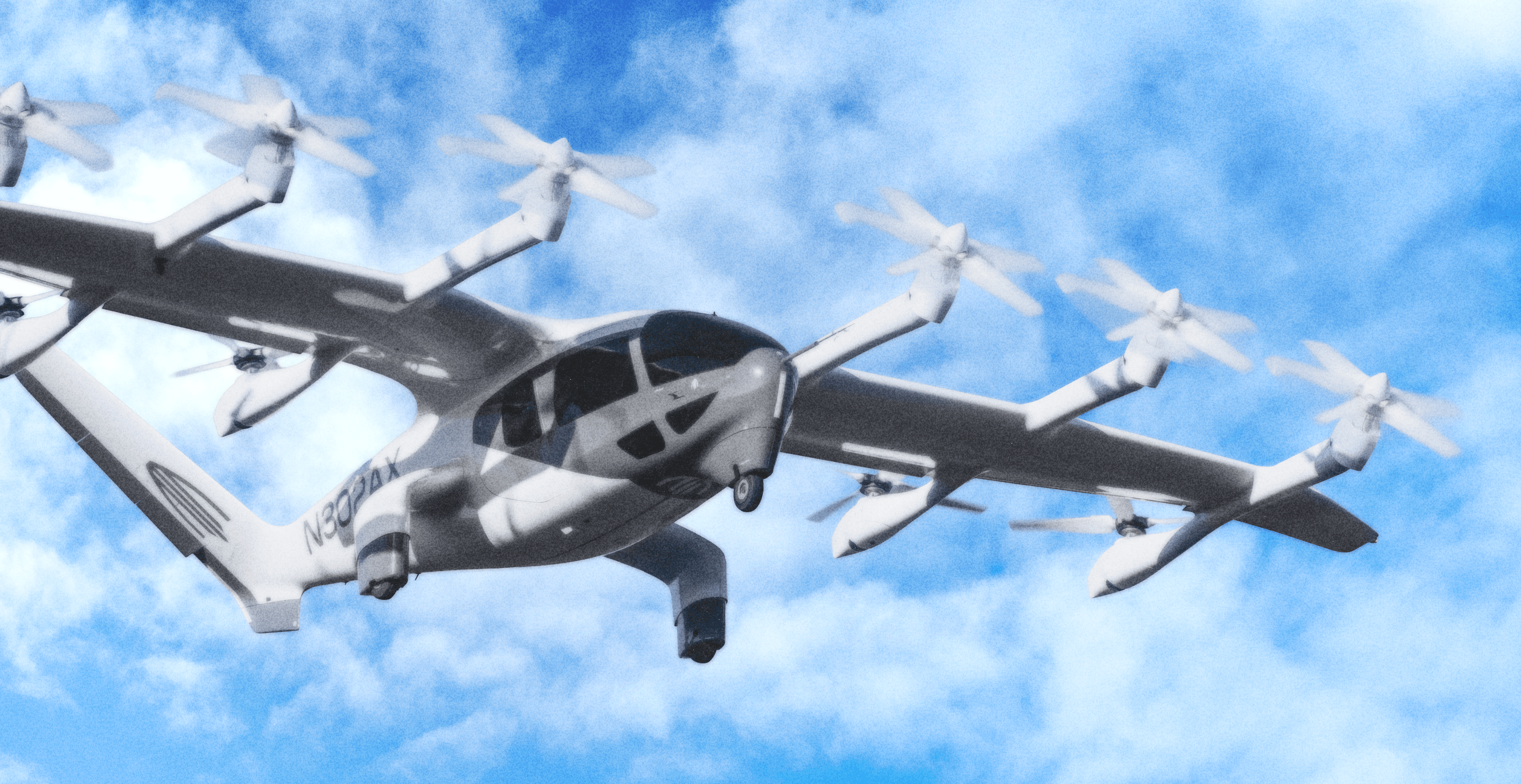

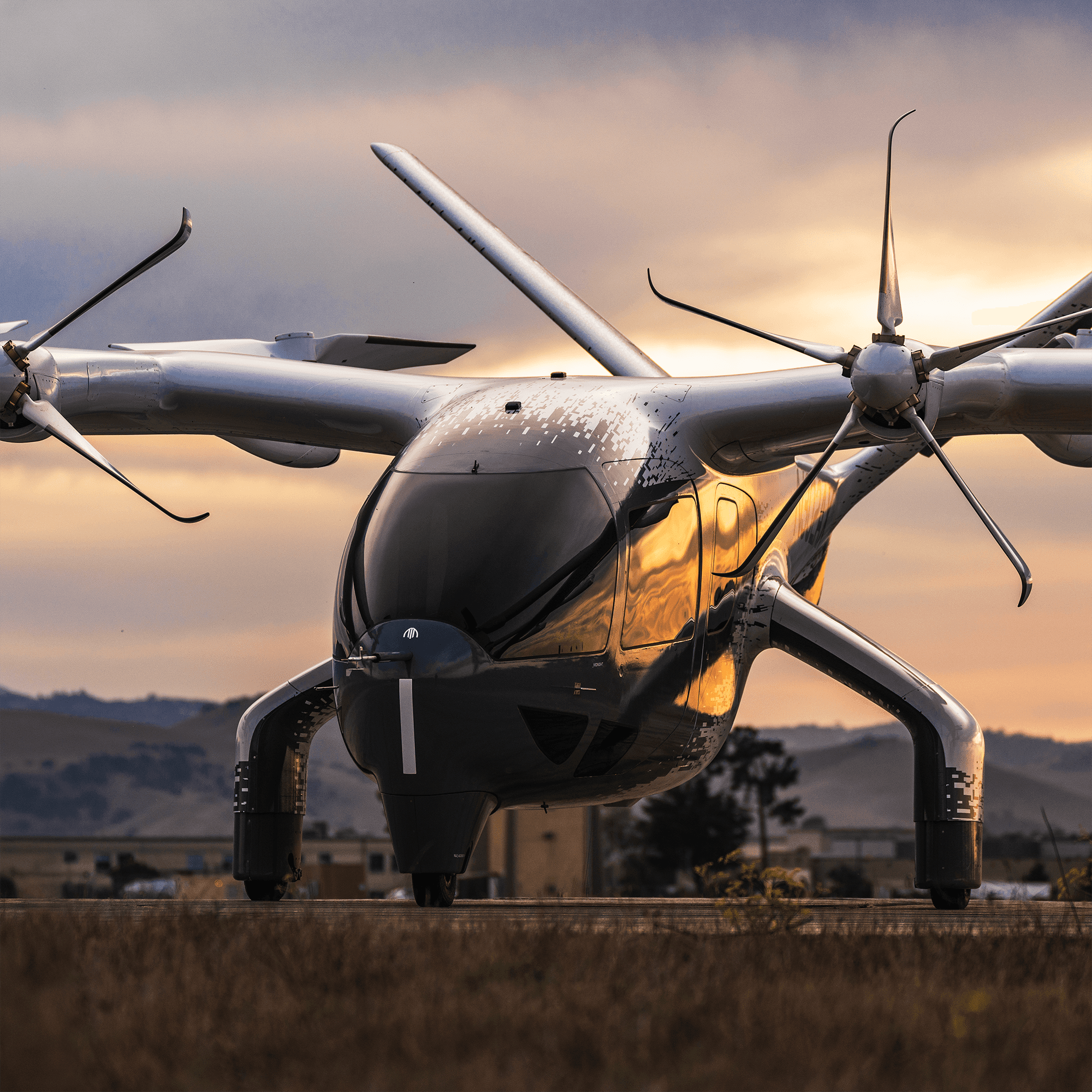

As the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris drew to a close last August, a lone eVTOL (electric vertical take-off and landing) aircraft flew for a few minutes above the gilded gardens of the Palace of Versailles. There were no passengers on board the German Volocopter aircraft, just some baggage. Pretty as the view might have been — for five minutes — it was an undeniable disappointment; Paris had pitched a vision of the air taxis whirring above its many boulevards, ferrying VIPs, athletes, and spectators to and from the venues. The French government approved a “vertiport” for staging such flights in the form of a barge on the Seine. But aircraft in Europe are approved (or not) by the European Commission, and Voloctoper failed to be certified in time. Less than six months later in December, the company went insolvent.

A fellow German eVTOL business, Lilium Aerospace, met the same fate (twice, actually!), and just recently its IP assets went up for auction. That auction was won, at just over $21 million, by a California company, Archer Aviation. As it happens, Archer had been previously selected the official air-taxi partner of the 2028 Olympics, which are to be held in Los Angeles for the third time.

Just recently, Archer agreed to acquire Hawthorne Municipal Airport’s ground lease for a hot $126 million. Hawthorne, situated just east of LAX and already embedded in the aerospace corridor that includes SpaceX’s headquarters, gives Archer a strategically located base for testing, staging, and ultimately operating air-taxi routes in the city during the games.

As an American who really wants to avoid a Paris repeat, a lot now hinges on the company to win FAA approval. So, I visited Archer’s headquarters in San Jose to talk with founder-CEO Adam Goldstein and inspect the hardware to find out more.

Goldstein grew up in Tampa, Florida. “Wonderful upbringing, very Southern,” he told me. “It was pickup trucks, guns, and country music.” Like many kids in the state, he assumed he would go to one of the three big Florida schools — “Florida, Florida State, or Miami. If you were rich, you went to Miami; otherwise you went to Florida or Florida State.” He chose the University of Florida, but by the time he graduated he was determined to leave. “I wanted to get out of there. I dedicated my passion to get to New York. I just wanted to be in a big city, see what the rest of the world looked like.”

New York was exactly what he wanted. He moved there and, in his twenties, became an entrepreneur. Silicon Valley had been producing generation after generation of tech companies, all clustered within a few miles — “Nvidia, Meta, Google, Tesla, Sun Microsystems… probably 50% of the S&P are within ten miles of this office,” he said. “But New York didn’t have that.” It enjoyed a 2010s miniature startup boom, though the companies were different — direct-to-consumer commerce startups like Warby Parker, for example. In New York, Goldstein was writing a blog about finding jobs in the New York technology & sales scene. The blog took off, and eventually became a software company, Vettery, a marketplace connecting job-seekers to businesses. In 2018, Vettery was acquired by a Swiss firm for a reported $100 million.

Goldstein told me it was always his desire to get into hardware. After selling Vettery, Goldstein went back to Florida, where with some of his new fortune he helped set up an eVTOL research lab at his alma mater, focusing on small-scale aircraft to test the fundamentals of electric flight. The main road running through Gainesville, Archer Road, gave the lab — and eventually, the company — its name. The team at the Archer Lab built and flew five- and ten-foot-wingspan prototypes to measure speed, range, battery performance, and the electric range equation (for comparison, the Archer Midnight’s wingspan is just under 50 feet).

Because batteries store far less energy per kilogram than jet fuel, every electric aircraft design must solve the same equation: does the aircraft carry enough usable energy to lift off vertically, transition to forward flight, cruise at speed, and still have the required reserves? In practice, this means testing how much range you get for every additional pound of structure, passengers, and batteries — and how different motor and wing configurations affect that tradeoff. As he puts it, an aircraft only works as a product if it has “enough speed, range, and payload that somebody would be willing to pay for it.” If it carries too little payload, or costs too much to operate, the economics collapse. “How do you as a consumer buy aviation products?” he asked me. “There are only two things you care about: safety and cost.” A cheap, bare-bones helicopter is perceived as unsafe; a luxurious twin-engine machine costs thousands of dollars for a flight of any length (“you probably won’t do that either.”)

Solving the dual aerospace-commercial equation was the purpose of the lab, and now the purpose of the company. “There are companies that build amazing tech and never get products to market… and there are companies like Tesla that are famous for shipping,” he said. “My version was going to try to commercialize it.”

An eVTOL Moment?

Adam posits that there are three major shifts that made it possible to build a massive, valuable eVTOL enterprise.

First: batteries. Improvements in energy density and power delivery meant electric motors could finally support aircraft-level performance. “By batteries getting better, it meant you could build these new electric power systems that could actually do pretty amazing things.”

Goldstein recalled Elon Musk’s refrain that “everything would go electric outside of rockets.” Traditional aircraft are locked into the tube-and-wing layout because they require a few very large, highly efficient engines. “Electric motors scale down without losing efficiency, which means you can distribute many smaller units across the airframe,” Goldstein said.

Second: geopolitics. Around the same time, the global aviation landscape shifted. “It became clear that the U.S. would not just automatically dominate aviation,” he said. “And in fact there were other countries like China that were doing very well. And the U.S. does not want to lose that position.” China’s aviation regulator remains the first — and so far only — authority to issue a type certification to an eVTOL.

Third: capital. Largely following the success of Tesla and SpaceX, investors were more willing to fund ambitious American hardware companies. The proof that a modern, vertically integrated transportation company could be built made it possible for firms like Archer (and Joby, another public company in the category) to raise the billions they have raised. Burn is high and revenue doesn’t exist yet.

As is the case with most new American hardware enterprises, Elon Musk is ever present, both as inspiration and often as a former employer of the talent. Many of Archer’s engineers come directly from Tesla and SpaceX. “He’s very inspirational as an entrepreneur,” Goldstein said. “He did things that nobody else could do. The rate of success that he had in some of the hardest problems was unlike anything you could find anywhere else.”

Highways in the Sky

“I want to build highways in the sky,” Adam declares, “that allow you to take off vertically and fly wherever you need to go. In order for that to happen, everything has to be autonomous. It cannot be done with pilots. It's too complex. The airspace is too complicated. Safety will never be there. But the good news is that the path to autonomy in aviation is actually quite well understood. The technology's there, the data's there to go do it. The challenge is the infrastructure.”

Communication with autonomous aircraft—say, diverting them for closed airspace, or giving complicated instructions—remains tricky. Cities need vertiports and rules for takeoffs and landings. The FAA’s decision to add a new aircraft type (the first in 60 years) was a big milestone; Goldstein thinks that progress in China was a major factor in that decision, and will be going forward as Archer and its competitors in the space seek certifications. At the moment, China is the only country whose aviation safety authority has actually provided a type-certification to an eVTOL aircraft.

“The US does have some things that are unique advantages that China does not have, and of course it’s true in reverse, too,” Goldstein said. “One of the things that we have that China does not have is a deep history of aviation excellence. If I want to hire a head of flight controls, a GNC (guidance navigation & controls) engineer, or an aerodynamics PhD that’s built a bunch of systems, I can do that pretty easily. That doesn’t exist to nearly the same degree in China. They just don't have the hundred-year aerospace history we have here.”

Archer’s lower-scale manufacturing is in California, with the capacity to build tens of aircraft per year. They do most of the testing in Salinas, California, a town that is most known as John Steinbeck’s home but which also hosts a large international airshow annually. In December, Archer completed construction on a 400,000 square foot facility outside Atlanta, Georgia, for higher-volume production (Goldstein says 650 aircraft per year, with an option to scale up to 2,000).

“We don’t really want to crank that volume until the certification stuff is done. I don’t want to build a bunch of planes only for them to change the rules.”

As for the demand for these highways in the sky, Goldstein offered me a thought experiment. How many times has the average person flown in a helicopter? His answer is either zero or once. But what does the world look like when flying‑once‑in‑a‑lifetime becomes flying once a month? “Just do the math,” Goldstein said, “think about how many aircraft you’d have to build. It's tremendous.”

The implications for defense are on his mind. For decades, the American way of war emphasized small‑volume, ultra‑capable systems. “All of a sudden it became very clear that autonomous and attritable was the future,” Goldstein said. “The old generation of wars were driven by speed, range, payload; the future [will be] won with autonomy at scale.”

Only about 5,000 Black Hawk Helicopters have ever been built, and current unit costs are about $20 million; about the same number of Apache helicopters have been built, and they cost $50 million. If Goldstein’s highways in the sky come to be, Archer could very well be producing that number in a single year. The existing aircraft, which are “complex, maintenance‑heavy, and designed to protect a human inside with layers of redundancy,” he said. “If you strip the pilot, embrace attritability, and go electric, costs fall.” (The planned price of Archer’s Midnight commercial aircraft is $5 million)

“In 1944, at the peak of WWII production, the U.S. built 96,000 airplanes. Today, across all categories, we’re at fewer than 5,000 per year," he said, seriously. “Rebuilding that capacity is a project for the century.”

About the Author

Maxwell Meyer is the founder and Editor of Arena Magazine, and President of the Intergalactic Media Corporation of America. He graduated from Stanford University with a degree in geophysics. He can be found on X at: @mualphaxi.