tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

Capitalism

•

Feb 10, 2026

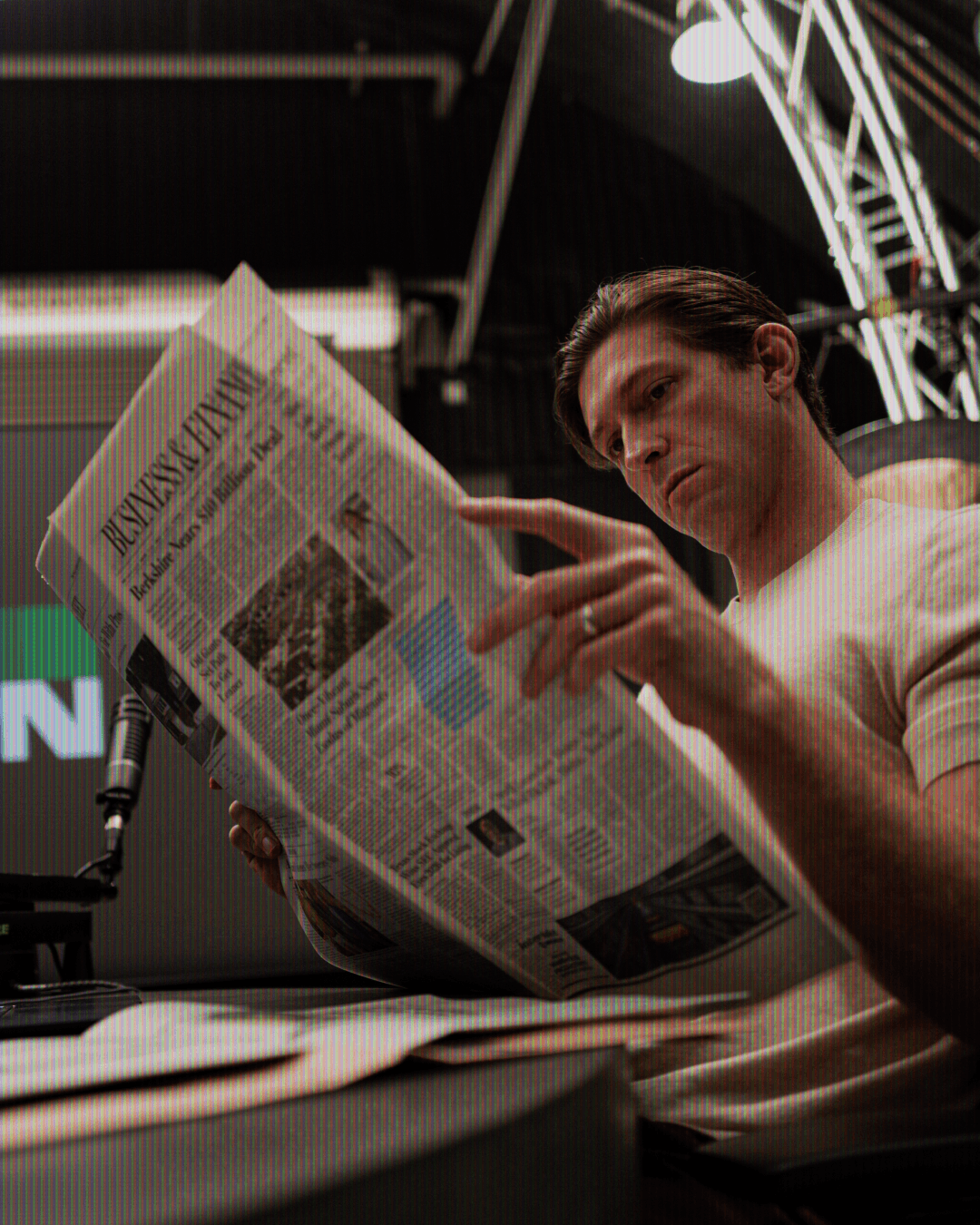

The Dorsey Thesis

How Edwin Dorsey made himself a name as a new type of market activist.

Free email newsletter:

Get Arena Magazine in your inbox.

In the Summer of 2017, Edwin Dorsey was enjoying time off from a year at Stanford when he heard a story about a bad experience with Care.com, the babysitting marketplace. A friend who had found work on the platform described encountering creepy families and a near scam. “You should look into the company,” he recalls her saying. Dorsey had interned at hedge funds and enjoyed corporate research, so he started investigating.

He found lawsuits claiming Care.com wasn’t conducting the background checks it advertised. “I thought, there’s one way to test this for myself: try to sign up as Harvey Weinstein,” he told me. It was October, and the avalanche of stories about Weinstein was in full swing. He used Weinstein’s photo, and the email ‘harveythebabysitter@gmail.com’.

The platform asked for his consent for a background check. “I say yes, and I’m documenting this because I wanted to be able to prove that I did this.”

To his surprise, “Harvey the Babysitter” was approved on the site. He made several other gag profiles, and wrote a report about it. The stock of Care.com fell modestly; in what may have been a coincidence, a board member left the next day. For Dorsey, it was the beginning of a major saga. It began when Stanford’s dean of students asked to meet with him.

“When I met with them, they initially said they wanted to meet with me about Wi-Fi policy violations,” he said. “I kind of assumed it was Care.com related, but wasn’t 100% sure.” The meeting revealed that a Care.com co-founder had contacted Stanford. Stanford told Dorsey that he had violated school Internet policy by pretending to be someone else, in this case… Harvey Weinstein!

Stanford warned that further complaints could lead to an ethics investigation, and Dorsey felt it was obvious they were asking him to take down the article. “As a young person, it was kind of terrifying because I had not gotten into any trouble at that point,” he said. He’d go on to publish a second article in June 2018 recounting both the Weinstein gag and a litany of other problems. By this time, he’d taken a position against the stock. He included in the report over 1,000 pages of consumer complaints relating to fake cheque scams, unauthorized billing, safety concerns, etc.

Care.com approved babysitters are linked to the deaths of at least five children (two of these babysitters had prior criminal histories, another was operating an unlicensed daycare)

Care.com babysitters have repeatedly abused children

Care.com’s caregiver screening appears to be nonexistent. For example, I was able to sign up and apply to babysitting jobs as Harvey Weinstein

Care.com’s background checks have approved convicted felons, prostitutes, and people on probation

Scamming is common on Care.com and some babysitters have received death threats

Care.com bills users for unused services and repeatedly bills customers after they cancel their accounts

Dorsey, for his part, was totally vindicated. A year and a half later, a headline in the Wall Street Journal read: ”Care.com Puts Onus on Families to Check Caregivers’ Backgrounds—With Sometimes Tragic Outcomes.” The stock cratered and the company was taken private less than a year later.

While Stanford never officially punished Dorsey, he encountered problems as a rising senior that, to this day, he thinks were not mere coincidences. In Stanford’s notorious housing draw, which no longer exists but for years determined housing for sophomores, juniors, and seniors, he received the worst-possible number out of all male seniors: 999 (1 is the best). So, while the vast majority of seniors had a draw number low enough to get a room to themselves, Dorsey ended up in a converted computer room not by himself but with two others. At one point that year, he lived in a motel for several weeks. “It was the lowest point mentally of my life,” he said. “I kind of just went insane from lack of sleep. I totally became the worst version of myself.”

Building The Bear Cave

Out of this turmoil came The Bear Cave, a newsletter Dorsey started in February 2020 to publish both roundups from the world of short research, and his own detailed reports. “I started the newsletter mainly as a way to get hired because I knew from my past experience that writing stuff online will get you attention,” he said. The Bear Cave started to grow, and eventually he decided he’d make it his job, rather than try to use it to get a job.

The Care.com episode was the first and last time that Dorsey actually took a position against a company on which he was publishing research. “I didn’t love the feeling of having a position against a company financially while also criticizing them,” he explained. So, he stopped, and monetizes his research by charging for access. In other words, he’s an activist but not a short-seller. “It’s a completely unique model, but I think it does come with higher integrity and a different set of incentives.”

At $640 per year with thousands of paid subscribers on Substack (and almost a hundred thousand total subscribers) I don’t need to tell you that The Bear Cave is doing well. At the same time, there’s no doubt that he’s leaving money on the table given how many companies featured in his reports have gone to zero.

The seemingly neverending bull market since 2008 has not been kind to anyone who is broadly bearish. American public equities are probably the greatest assets of all time. But what’s true in the macro picture is not always true in the micro picture, and it’s as good a time as ever to be looking for problems. Short-sellers on Wall Street have attracted an immense amount of attention, not all of it positive.

Michael Burry, the reclusive doctor-turned-investor was immortalized in The Big Short for having bet against the US housing market on the eve of the Great Recession — making billions for his firm and investors. In what may be the most well-known segment of business television in the 21st century, Bill Ackman and Carl Icahn clashed on CNBC over Herbalife and Ackman’s $1 billion short against it. Icahn called Ackman a “crybaby in the schoolyard” and pledged to create “the mother of all short squeezes.” Icahn won, and Ackman would exit the position five years later with a loss of about $1 billion, about as much as Icahn’s gain.

In 2021, GameStop became the epicenter of a massive, coordinated short squeeze by retail investors on platforms like Reddit’s WallStreetBets. Hedge funds shorting GameStop, of which there were many, were wrecked as shares soared from ~$20 in early January to a peak of $483 by January 28. Those retail investors were delighted to see the short-money collapse, not because of some earnest optimism about GameStop’s future cashflows, but to see those they perceived as elite market manipulators get a taste of street justice.

I bring up all of this chaos as a way to explain why Dorsey is quite happy to publish his detailed research and leave it there, rather than deal with the conundrum of short-selling in public.

“In a market built on froth and exuberance and everybody making money, shorts are some of the few people really incentivized to root out the bad conduct,” he said. “I think of the 22 companies I wrote about in 2021, all but one ended down on the year. There was so much low-hanging fruit.”

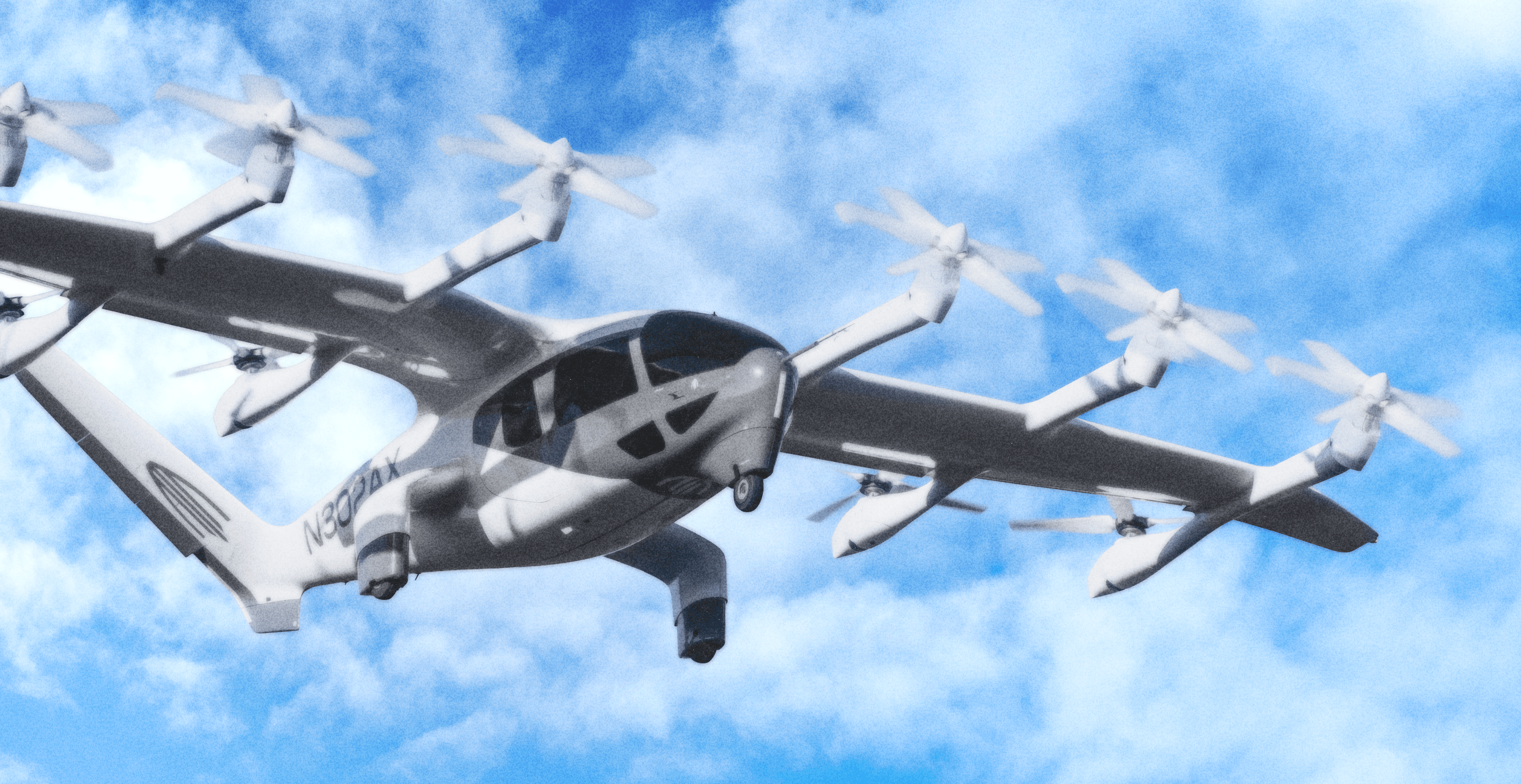

One such business that went was a drone company, AgEagle, whose stock soared in 2021, valuing it around a billion dollars. Dorsey decided to take a look. “There’s 10 employees, they only spent $40,000 on R&D. I looked at the product and it was literally a remote control plane and a GoPro. It was so clear it wasn’t a real company. Those types of companies only get pumped up when there’s a lot of froth and excitement and there’s making money and retail’s piling in.” When Dorsey published his report on February 18, 2021, shares traded above $10,000 each; today the stock sits at about $1.

To surface issues, Dorsey combs through public records, company filings, and consumer complaints acquired via FOIA requests. “The one thing I’m uniquely good at is going to state AGs and getting consumer complaints people file against businesses,” he says.

Other theses — the ones for which Dorsey has become more well known — aren’t so much about misconduct as they are about long-term trends. Like Hershey, of which Dorsey wrote in 2023: “Investors view Hershey as America’s dominant chocolate company, a safe bet with over a century of consistent growth, and a richly valued royalty on chocolatey cravings. Those days are over. Today, Hershey faces rapidly growing competition from one of the world’s youngest, most talented, and most influential entrepreneurs: 25-year-old YouTube star Jimmy Donaldson, AKA MrBeast. His new chocolate brand, Feastables, has waged an all-out war against Hershey in retail and on social media — and is winning. The Bear Cave believes Feastables rapid growth will soon take a major bite out of Hershey’s profits.”

MrBeast himself responded to the report, saying, “I wouldn’t recommend shorting a company, seems lame. But I will say these next few years between Feastables and Hershey’s will be interesting once I actually ramp up.” And ramp up he did: in 2024, MrBeast’s Feastables did over $250 million in sales, with profits of about $20 million (1% of Hershey’s profit in the same year).

“It was one of the most mocked reports I ever did,” Dorsey said. “You can just see so many people calling me an idiot.” He stands by the thesis. “My writing about how Mr. Beast's Feastable brand is going to take share from Hershey's over time is not going to impact Hershey's stock from day to day. It's not going to send the stock down 10%. So, that wouldn't work in the activist short model. It does work in the newsletter model, because the thesis is about long-term disruption.”

In the last three years, Hershey has significantly underperformed the S&P 500; its market capitalization today is about $35 billion, versus the $50 billion when Dorsey published his thesis.

A similar Dorsey thesis was Draftkings, which Dorsey thinks stands to be seriously hurt by prediction markets. “The prediction market model is a lot less profitable than the traditional sports book model for the company owner. So I think DraftKings is hugely in trouble.”

One large company where Dorsey wishes he’d held his powder was Palantir. “The worst report I ever did was critical of Palantir. I would say for me that was one where I kind of relied more on what friends in the tech industry were telling me than really understanding it myself.”

“I described it as a black box,” he told me. “but in this case there was a lot of value in the black box. I focused a lot on its deals with SPAC companies that increased its revenues. It was all factually accurate but it kind of focused on an issue that didn't matter at the expense of one that did.”

“Bigger companies can take a lot more time to get right,” Dorsey said. “There are large companies that I've followed for many years now, and I still don't think the timing is right, but one day there will be an article.” On the other hand: “Smaller companies tend to be much shadier and have much more egregious issues than big companies. So I can write a Bear Cave on a small-cap with egregious issues pretty quickly.”

As it happens, Dorsey’s biggest actual stock holding is in a casual pizza restaurant chain. I remembered Dorsey telling me this a few years ago, and thought it was an amusing fact. So, I asked him why: “It's very rare for a $50 million company to have a clean balance sheet, profitable operations, and a very talented CEO. So that's something that just excites me."

The Prediction Market Frontier

A recent interest for Dorsey is prediction markets, where he sees a new frontier for truth. “The product of prediction markets is information,” he says. Unlike media outlets with competing incentives, prediction markets reward accuracy. “There is one and only one incentive, which is being right about the information or the question at hand.” He’s an active participant, and thinks his income from prediction markets may soon exceed income from The Bear Cave, which is itself safely in the seven-figure range. “There’s a huge societal benefit to having good quantitative data on these important questions,” he said, “like whether some legislation is going to be passed. That’s hugely useful to executives trying to plan.”

And soon, he says, “the world expert in certain things isn’t going to be some guy on CNBC. It’s going to be the guy who’s in the middle of nowhere but has predicted the CPI prints perfectly for the last three years. Prediction markets are going to find those people.”

About the Author

Maxwell Meyer is the founder and Editor of Arena Magazine, and President of the Intergalactic Media Corporation of America. He graduated from Stanford University with a degree in geophysics. He can be found on X at: @mualphaxi.