tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

Capitalism

•

Dec 16, 2025

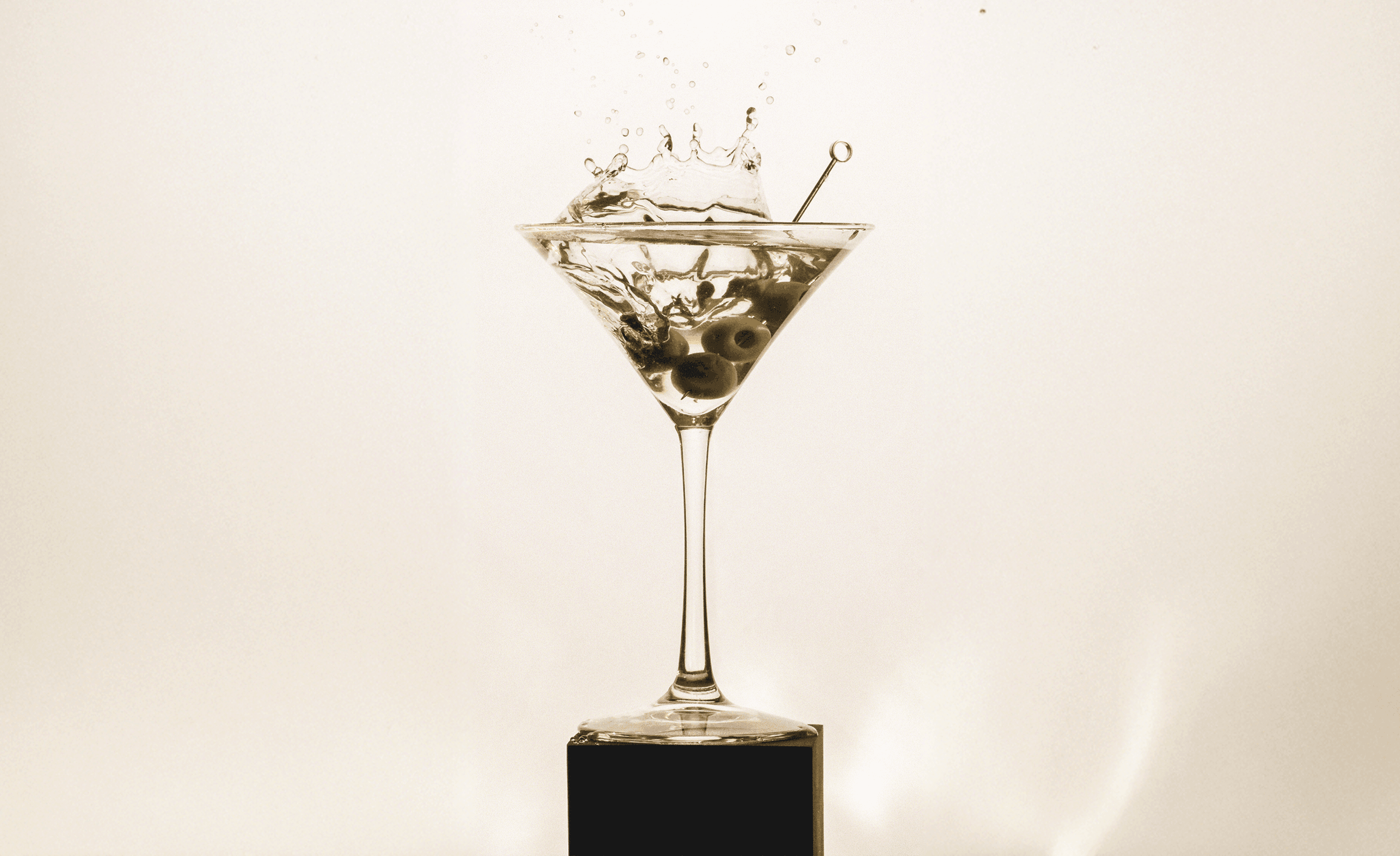

Dirty, Twisted, Shaken, Dry

The mythic origin of the martini

by

Free email newsletter:

Get Arena Magazine in your inbox.

The earliest reference to the “three-martini lunch” comes from a 1954 article in The Atlanta Constitution describing long lunches enjoyed by retirees and expense‑account men. By 1960 the term had become a marketing trope; a clothing advertisement bragged that its suits could endure the “now‑famous three‑martini lunch.”

In the meal’s heyday in the mid-20th century, businessmen would shake hands, make deals, and generate shareholder wealth over a white tablecloth three-martini lunch. By the end of the century, the ritual faded, the three-martini lunch attacked as a symbol of excess and inequality.

As the three-martini lunch has morphed into the rush to grab a bowl, some important dignity and civility of business has been lost. As it happens, so has the origin of the martini. It undoubtedly rose because of its association with corporate glamour, but nobody really knows where it started. Given the martini’s strength as a symbol, its origin is an event primed for mythmaking.

One theory traces the origins of the drink to a bartender in the 1850s at San Francisco’s Occidental Hotel, who was asked to make something special for a miner heading to “Martinez,” a town about forty miles east of San Francisco. The bartender mixed Old Tom gin (a particularly sweet gin), vermouth, bitters and Maraschino liqueur; his customer’s slurred request for a “Martinez” became “Martini” across the bar. A competing story flips the geography: a bartender in Martinez is said to have invented the drink for a miner heading to San Francisco. These dual tales appear in almost every account of the Martini’s history, from Difford’s Guide to cocktail lore, because they mirror the 19th‑century Gold Rush’s restlessness and uncertainty.

And then there is the Knickerbocker legend: a bartender named Martini di Arma di Taggia, tending bar at New York’s Knickerbocker Hotel in 1911, mixed gin and dry vermouth for John D. Rockefeller himself. This story has the perfect setup: the richest man in America drinking what would become America’s richest cocktail. It is almost certainly apocryphal, given early recipes of the “Martinez.” Still, the myth clings. Given a century-long association of martinis with finance and old money, it makes aesthetic sense that the martini would come not from the Wild West but from a hotel lobby overlooking the great American financial center. Both the quest to find gold out west and the drive to create capital out east root the martini’s history in one of hard work. Only the type of work (rugged and exploratory versus streamlined and corporate) differs.

The early formulations of the martini resemble a gin Manhattan: Old Tom gin, vermouth, orange curaçao or maraschino, and bitters. The first printed recipe for a cocktail called the “Martinez” appears in O.H. Byron’s 1884 The Modern, decades before the Knickerbocker legend. The Martinez was essentially a fortified wine cocktail anchored by gin; the sweetness reflected not just available ingredients but also the 19th‑century palate. As the drink travelled east, the recipe changed and the name morphed from Martinez to Martine and eventually Martini, perhaps because American bartenders associated the cocktail with the Italian vermouth brand Martini & Rossi. Naming is never innocent; to call it a Martini was to tie it to an aspirational European sophistication and a global trade in spirits.

By the turn of the 20th century, the martini underwent a sleek rebrand. Difford’s historical survey notes that early recipes contained two parts gin to one part sweet vermouth, but by 1904 Stuart’s Fancy Drinks and How to Mix Them recommended Plymouth gin with French dry vermouth, signalling a shift toward dryness. (A cocktail is ‘dry’ if it is not sweet, when all the fermentable sugars in a drink have converted into alcohol.) The first printed reference to a dry martini appears in Frank P. Newman’s 1904 French bar book. As cocktail historian David Wondrich observes, this ‘dryness’ was partly a marketing innovation: the Italian vermouth maker Martini & Rossi promoted its product for “dry cocktails,” and the rise of London Dry gin, which was simple, juniper‑forward, and industrially produced. But ‘dry’ drinks felt less indulgent and more restrained. The sugar of Old Tom gave way to the austerity of dry gin. During this time, the lemon peel was the garnish of choice for the dry martini, a holdover from the sweet martini precursor in Harry Johnson’s Manual.

As time went on, the martini’s dryness only intensified. By the 1920s and 1930s the martini ratio shrank to 4:1 or even 15:1 gin to vermouth. During Prohibition, like all drinks, the martini went underground, but new forms of the drink continued to evolve. As the drink gained popularity in the United States, the British novelist W. Somerset Maugham insisted that a martini must be stirred, not shaken, so that the molecules “lie sensuously on top of one another.” Shaking, on the other hand, popularised later by James Bond, signals the modern appetite for speed and spectacle. In Dr. No (1962), Bond’s order of a “vodka martini, shaken, not stirred” propelled the vodka martini — all that’s changed is the base spirit — to global fame; Tom Sisson of the New York Bartending School argues that Bond’s order made the vodka martini the predominant form of the drink. A 2000 Vanity Fair article claims that a Lebanese barman at the Colony, a Manhattan restaurant and gathering for high society that operated from 1919 to 1971, was the first to shake, not stir, vodka. Vodka’s purity and flavor and minimalism was the perfect base spirit for a professional drink; its dryness made the drink feel productive, not excessive. Lacking sugar and juice, the martini — either gin or vodka — read as ‘serious’ and thus ‘corporate.’

By the mid‑20th century, the martini became the drink of the American elite.

But, this martini was specifically the dry martini that was allegedly served at the Knickerbocker Hotel and served to John D. Rockefeller; it was made from gin and dry vermouth, with bitters optional. The phrase “three‑martini lunch” did not appear in print until the 1950s, but when Wall Street and Madison Avenue adopted the drink, it became synonymous with efficiency and taste.

In a 1978 address to the National Restaurant Association, Gerald Ford summarized: “The three-martini lunch is the epitome of American efficiency—where else can you get an earful, a bellyful, and a snootful at the same time?” Businessmen claimed that their creativity increased post-three-martini lunch. At white tablecloth steakhouses, olives were served as martini accoutrements: as an imported European delicacy, the olive added to the martini’s high-class reputation. The early martinis were smaller at around two and a half ounces, only a third as intoxicating as contemporary versions. The three‑martini lunch emerged from this environment: a perfect accompaniment to a long midday meeting where deals were made and class distinctions affirmed. One can imagine going back into the office after a 1950s three-martini lunch (now equivalent to one martini in 2025) only slightly tipsy and ready to keep working.

But as the three-martini lunch became a symbol of pinstripe-suited corporate America, a target was placed on the martini’s back (and the back of the well-heeled executives who liked to charge their long lunches to the corporate account). In the 1970s, the three‑martini lunch also became a political symbol of runaway capitalism. When stagflation plagued the American economy, President Jimmy Carter denounced business meal deductions as an abuse of the upper class, saying that the “working class was subsidizing the $50 martini lunch.” Conservative writer William F. Buckley Jr. responded that the martini had become “a code word” used not to protect tax revenue, but to attack a pro-capitalist lifestyle that personally offended Carter, an especially prescient attack during the Cold War where being branded ‘anti-capitalist’ was a political liability.

But the “three-martini lunch” struck a nerve; the debate over whether elaborate corporate meals ought to be tax deductible continued for decades. Presidents Gerald Ford and Donald Trump supported allowing businesses to deduct 100 percent of meal costs; John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan and Carter, odd bedfellows, opposed it. A 1942 tax reform that prevented “lavish or extravagant” business expense deductions was solidified in the 1986 Tax Reform Act, which proclaimed that “No deduction shall be allowed for any activity of a type generally considered to constitute entertainment, amusement, or recreation… if such activity is lavish or extravagant under the circumstances.” This language governs business expenses to this day.

Three-martini lunches are now a relic. And, drudging through the stagflation that ruled the 1970s economy, corporate entities did not want to foot the bill for “lavish or extravagant” lunches amidst economic uncertainty. Today, young professionals pay for their own espresso martinis from their own pockets rather than ordering dry martinis midday from a bottomless expense account. But the business lunch never left, it just changed clothes. Yes, Sweetgreen is less glamorous than the white-tablecloth settings of three-martini lunches. But, the kale salad is just the martini inverted: instead of demonstrating your immunity to toxins, you demonstrate your immunity to pleasure.

Before 1987, every dollar spent on three-martini lunches could be written off against business income. Now, these meals are only fifty percent deductible. Worse yet, they’ve become unfashionable. Now, 62% of workers report not leaving their desks at all for lunch. The end of the three-martini lunch era marked the beginning of a sterile, overly-professionalized work environment. Bureaucracy’s fight against corporate excess has pushed away a human element in business. No one was harmed by these long business lunches, unless a participant had a low tolerance for vodka.

This article appears in Issue 006: Three Martini Lunch. Subscribe to get it in print!

About the Author

Yi Ge is a sommelier-in-training based in San Francisco, where she works at a two Michelin star restaurant. She can be found on X at: @phones111111.