tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

Capitalism

•

Dec 23, 2025

A Small Town Capitalist Christmas Story

A Corner in Arizona, a Leg Lamp in Oklahoma...

Free email newsletter:

Get Arena Magazine in your inbox.

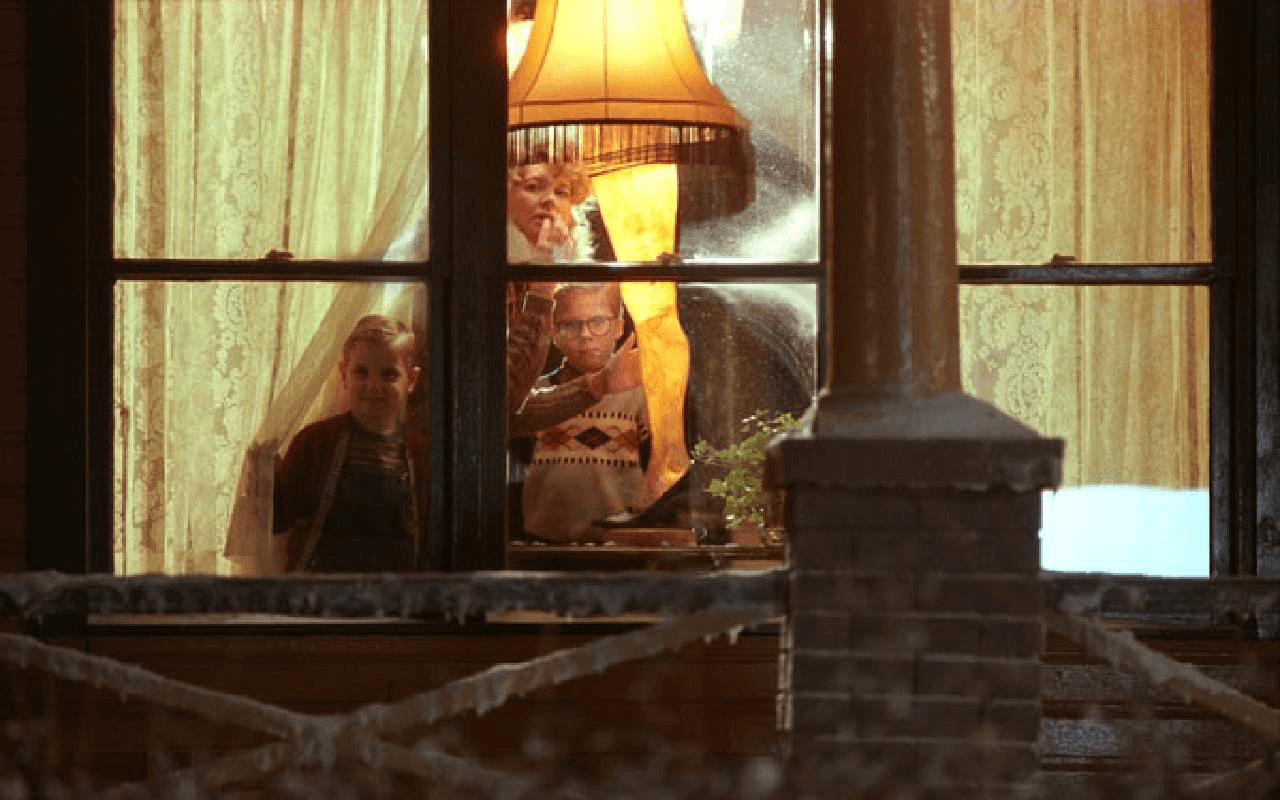

”A female leg, full size, wearing a black stocking and a high-heeled slipper, with a black fringed shade sitting on top of the thigh. A gorgeous, silk-stockinged, high-heeled female leg, in living color, sticking up in the air like some great baroque exclamation point. A leg lamp!....It was the soft glow of electric sex gleaming in the window.”

When Jean Shepherd wrote those lines in his 1966 short story, which became the basis for the beloved film comedy A Christmas Story (1983) there was no way he could have imagined his lascivious description would spark intense debate and genuine hard feelings throughout the small town of Chickasha, Oklahoma (pronounced chi-kuh-shay) nearly six decades later. How could he?

It was just a leg lamp. A one-off. A punchline of bad taste, delivered to illustrate working-class American life in the 1930s-1940s and the “major award” culture of the time. The leg lamp exemplified the burlesque aesthetic that exploded in the 1940s. Novelty furniture pieces shaped like naked women were actually sold as “man cave” or bachelor-pad decor and were considered naughty or risqué, if not a little low-class. And in contests directed at men, the prizes were often gaudy, oversized or even borderline vulgar — perfect for the snickering little boy deep inside them.

Shepherd’s father had won just such a contest, taking delivery of his own 100% genuine leg lamp. He displayed it proudly in the family’s living room window, declaring to all his masculine bonafides and his undeniable status as a “winner.” Predictably, his wife hated it, his neighbors complained, and eventually the lusty light “accidentally” ended up broken. But its place in the classic film clearly struck a chord that resonated with people over the years, resulting in the horrifically tacky leg lamp somehow becoming a beloved piece of Americana.

Shepherd’s loving retelling of his adventures with “the Old Man” were an almost verbatim account of events he personally experienced growing up, often saying that almost 90% of the movie actually happened. You can’t fake sentiment, and A Christmas Story has that in spades. Viewers could feel it.

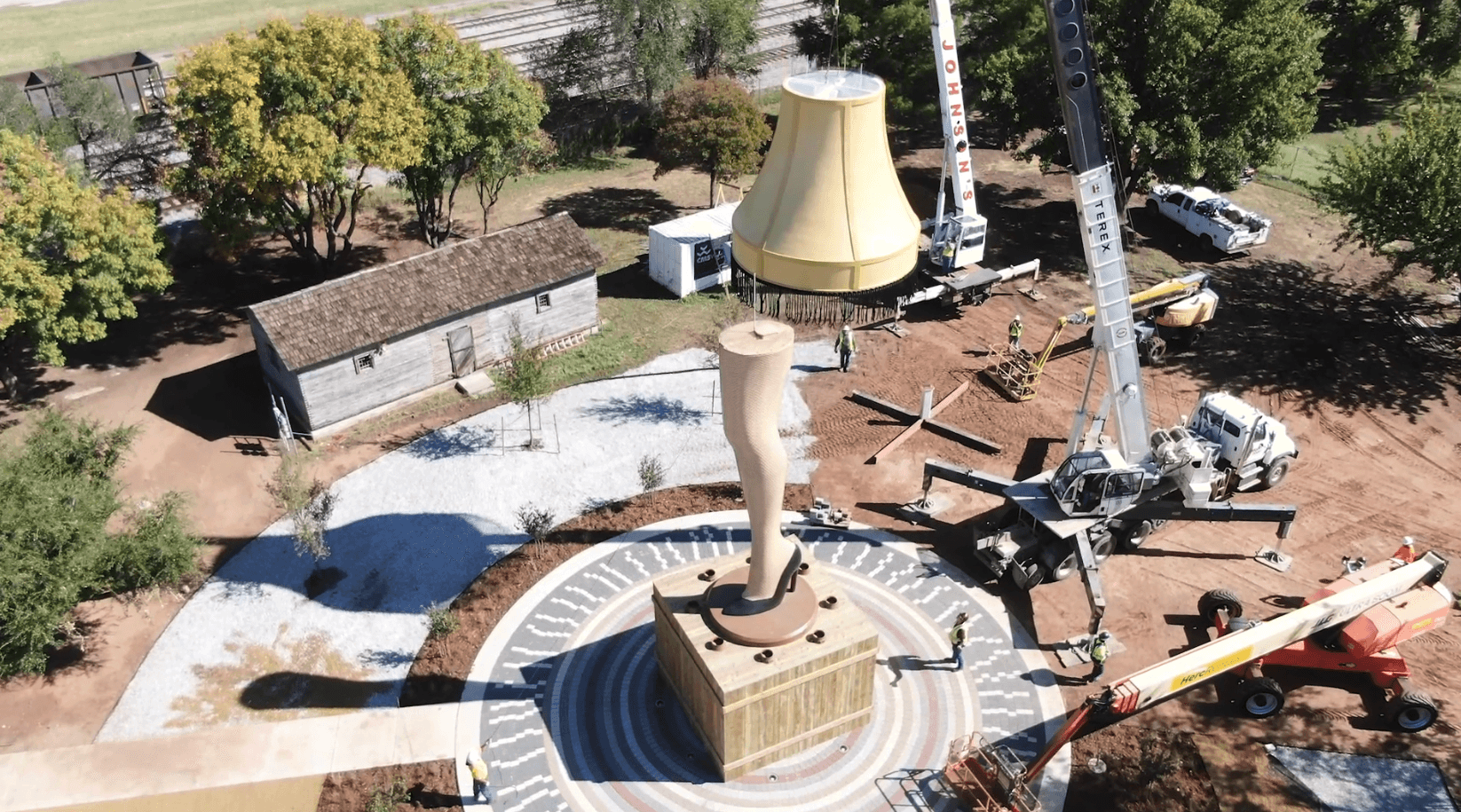

So, when Chickasha business owner Tim Elliot proposed the installation of a five-storey leg lamp to entice tourists to stop in his small town off Interstate 44 and spend some money, he thought it was a no-brainer. Everyone else just thought he was crazy.

“Some people said they were not gonna live in a town that had a leg lamp,” said Elliot. “…I want Chickasha to be a fun place to live [and] raise a family.” He wouldn’t abandon his quest to put a fifty-foot leg lamp in the middle of town. He knew the lamp’s iconic stature could make a huge difference in the town’s future, but it was not without cost. The incredible details of this clash can be found in a fascinating documentary by filmmaker Reagan Elkins, himself a product of small-town Oklahoma, where he digs into the realities, larger-than-life personalities and the struggles that surrounded almost every aspect of their leg lamp adventure.

“I really can’t believe this is happening,” says Elliot, looking up as the leg lamp came together.

Objectively, trading in kitsch is usually a bad idea. Fads can change quickly and when the parade finally moves on, who wants to get stuck with something stupid or embarrassing in their town square? At the end of the day, is it worth all the trouble?

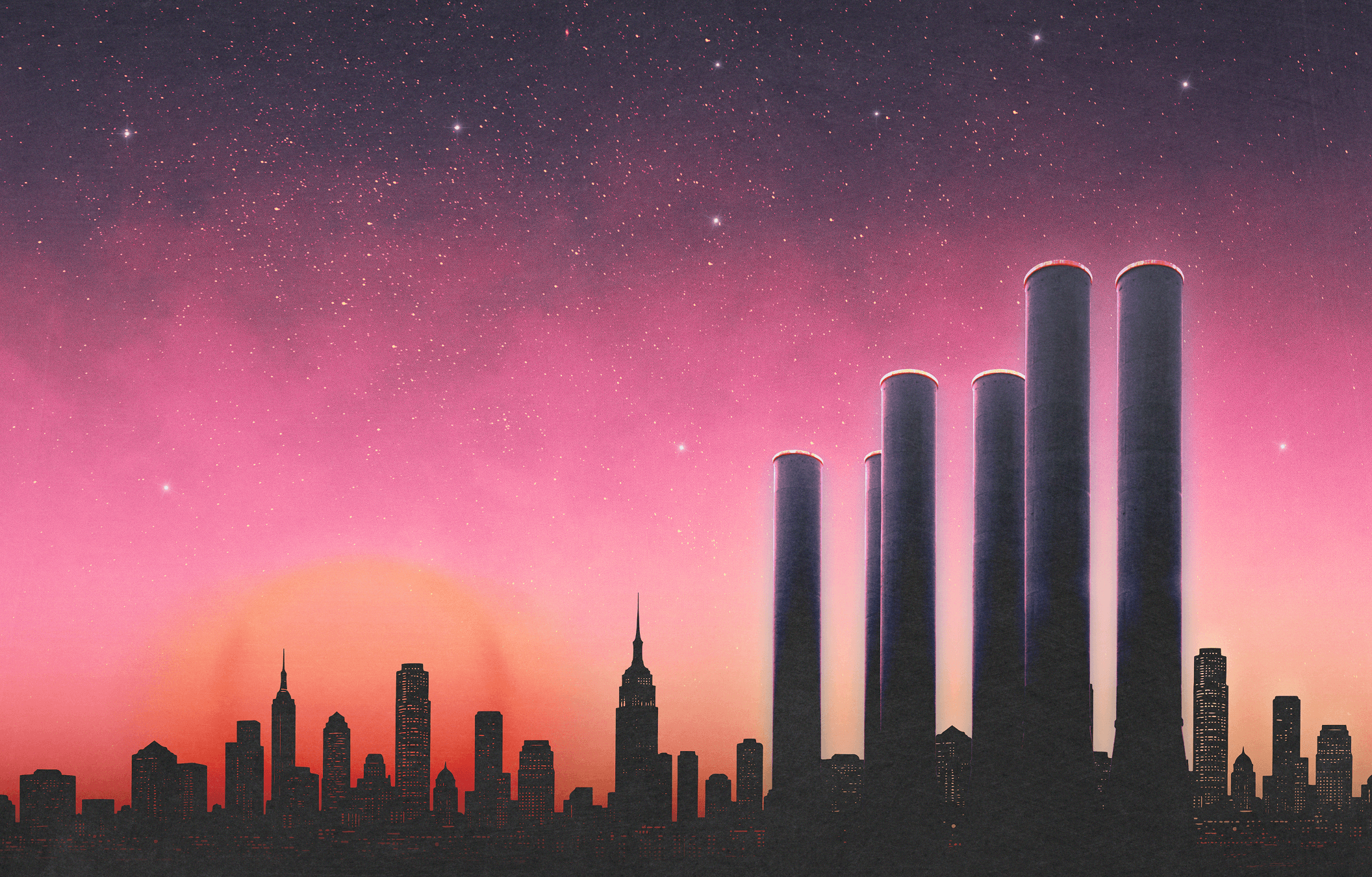

Small Town, USA

Small Town, USA (that is, cities or towns with populations fewer than 50,000) are usually only able to fund infrastructure projects like bridges, roads, and community centers through a combination of local, state, and federal sources. If they want to do things differently, they need to have the funds on hand to make it happen. But that’s not easy these days. Total public infrastructure spending as a share of GDP, declining steadily since the 1970s, has hit rural areas the hardest. As older residents die, younger folks move away, and physical assets like infrastructure age; rural communities are struggling to keep up with higher per-capita costs just to maintain a decaying status quo.

Additionally, thanks to a run of outsized property tax increases during the seventies, many states voted in propositions to limit or even freeze property tax increases to protect homeowners and retirees on fixed incomes, leading to smaller revenue streams overall. It was logical at the time, and made a direct impact, but did have the effect of kicking the can down the road for future generations to deal with. Or at least forcing future generations to find alternative funding sources, which is why state-shared sales-tax revenue became critical. The small towns made generous use of the funds when available, which it most certainly is so long as the economy is stable. But when recessions hit, the money dries up fast;city services and infrastructure needs take a beating. That means small towns needed new and creative ways to bring in extra cash.

Winslow's Second Meteor

For most of its existence, Winslow, Arizona was known for a nearby meteor crater, at least until a shaggy haired musician had his car break down in Flagstaff. Looking around, he noticed a girl in a truck slowing down to check him out. Pleased, but still bored, he sat down and worked on a song, eventually deciding nearby Winslow, about an hour drive away, sounded better lyrically than Flagstaff.

Back in Los Angeles, the musician, a young man named Jackson Browne, showed his song-in-progress to the upstairs neighbor, who tied up the second verse with the memorable line, "It's a girl, my lord, in a flatbed Ford, slowin' down to take a look at me." The neighbor was the singer Glenn Frey, and he asked if his new band The Eagles could record the song.

“Take it Easy” became their first single and a monster hit.

Eventually, Winslow embraced its pop culture fame, creating the "Standin' on the Corner Park" in 1999 at the corner of Old Route 66 (W 2nd St) and Kinsley Ave with a sign, a mural, a parked truck and, in time, a couple of bronze statues.

While exact revenue attribution is tricky, estimates suggest the park attracts 100,000–200,000 visitors annually, many via Route 66 road trips, peaking during the annual September Standin' on the Corner Festival. Economic impacts of up to $5 million per year are claimed, a far cry from the broader decline and difficult times the town of 9,500 suffered when Interstate 40 first bypassed Winslow back in the 70s. Tourism bucks, compliments of a classic hit song and the long tail of memories it contains, now help to keep Winslow, AZ shiny and bright. Amidst a rapidly changing present, pop cultural memories maintain powerful holds, becoming like traditions of old — touchstones we are unwilling to let go of and determined to share with those coming after.

Hope, Canada

In 1981, a town in British Columbia, Canada was used to film a new Sylvester Stallone movie called First Blood. It was the biggest thing to ever hit the tiny city of 3205, and when the character of Rambo, a U.S. Army Special Forces Veteran, went on to become just as big culturally as Stallone’s Rocky character, Hope, BC basked in the glow of its personal affiliation with the all-new legend.

Amazingly, over the years, tourists kept coming to Hope. And thanks to annual pilgrimages made by curious fans of First Blood, the cafes, gas stations, and shops of Hope have enjoyed a sustained economic benefit for decades.

The best data comes from the 40th anniversary celebrations of First Blood held in October 2022. Three days of walking tours, screenings, contests, a statue unveiling and more generated almost $800,000 CAD for Hope’s economy. The town estimates the 15,000-plus Rambo fans who visit annually generate an economic benefit of $1.5-$3 million CAD.

The Triumph of the Leg Lamp

But a silly leg lamp? Why should a few scenes from an eighties movie be considered “culturally significant?” To be fair, what is our culture anyway? In many ways it’s a shared collection of events and experiences that make up our group memories. And with the current partitioning and grouping of societies through curated social media, on-demand films and personal music playlists as compared to old school newspapers, TV networks and radio stations, what would even qualify as a “group memory” three or four decades from now anyway? The answer is that we won’t know until it happens. Which is why the leg lamp is such a perfect example of our current age.

We have seen recent traditions (9-5 jobs, static meal times, religious observance) fall by the wayside. As people we are hardwired to find new things to replace them. So parents in their 40s-50s are going to treat their favorite films or music or memories as devoutly reverent as anything their own parents held dear. Heaven help us when the Kardashian generation starts handing that group of memories down.

Tim Elliot and several other true believers in Chickasha continued their march forward, determined to bring the massive leg lamp to fruition. A first iteration of the project was a giant inflatable leg lamp which led to weather issues (blown over in high winds, drooped and saggy during the heat) plus a need for constant repairs. The leg lamp was even stabbed at one point. A local firm was thus contracted to make a permanent fibreglass version that took two forty-foot cranes to lift into place.

At the same time, legal threats arrived from Warner Bros. demanding an immediate halt to its use. Thanks to some creative planning, that particular challenge was able to be ignored due to its placement on university grounds instead of civic lands. Not only did that qualify the piece as an “art installation,” but it also had the effect of removing the city council’s ability to determine its future, something that came as quite a surprise to some folks — the haters.

Along the way, Elliot’s group somehow discovered a local man who claimed (with documents) to have designed the very first leg lamp ever, thus creating a direct, Chickasha connection that emboldened them further. Was it dubious? Perhaps, but the tenuous local connection was more than enough to keep the project moving forward to completion.

Through it all the leg lampers endured the anger and disdain of fellow citizens as well as a general skepticism about their aims. Would it actually work to bring in tourists who would spend money or was it doomed to be a cautionary tale for other towns thinking “outside the box”?

As always, capitalism speaks for itself. The leg lamp’s numbers tell its tale. As of 2023, Chickasha became the top US seller of licensed Christmas Story items. While the leg lamp may seem like little more than a silly curiosity from a niche movie, Chickasha has seen an additional 50,000 tourist visits per year. New businesses have opened, the city has received direct investments of more than $5 million, and tourism’s economic impact averages between $3-$5 million per year.

Is this really the future for propping up small town finances? Tim Elliot certainly thinks so, pointing to the mini tsunami of media attention and the dramatic increase in tourism and local spending Chickasha has enjoyed.

In fact, he’s already teasing his next big idea: Blazing Saddles. So far he hasn’t offered anything beyond repeating the movie title. It is known that Cleavon Little (the star of Blazing Saddles) was born in Chickasha but beyond that, Elliot has not shared his vision for his new attraction. Will it be insane? Maybe. A little tacky? Perhaps, but the success of the leg lamp means he deserves at least a little consideration, right?

But what if the next idea tanks? What if it’s exactly the wrong thing for the tourists Chickasha so desperately wants? That’s kind of the self-correcting beauty of this form of pop-cultural capitalism. If you get it right, you are rewarded; if you get it wrong, the people will let you know and the money won't flow in. It won’t be a mystery, that’s for sure. If you try to make something a “thing” that is not actually a “thing” it won’t work. Through their dollars, tourists are telling Hope, BC that Rambo still matters. That’s why they come. Same with Winslow, AZ. Chickasha can see the people coming. They will be the first to know when it stops.

These capitalist realities speak to an inherent purity that must exist in endeavours such as this. When you’re playing on the turf of nostalgia and memories, you better tread carefully and behave with the utmost of sincerity. You can’t fake sentiment. So, if you build the right shrine to folks’ memories, they will come in droves. But, if you do it callously or even with an underlying hint of cynicism, you will pay the price. And what could be more overtly capitalistic than that?

About the Author

While writing has been a constant for more than three decades, Jarrod Thalheimer has also seen service as a hotelier, actor, security guard, union leader, hot receptionist, truck driver, scrap metal chucker, land manager, movie producer, paper boy & more. Vixen: A Maggie Deacon Adventure is his first novel.