tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

Civilization

•

Feb 5, 2026

Among the Bitcoin Missionaries

A visit to the Palestra Society in San Salvador

Free email newsletter:

Get Arena Magazine in your inbox.

Flying out of Miami in March 2024, it's the sort of hazy purple tinted golden hour that only happens when you're closer to the Southern Hemisphere. The lights were warm. Flying into San Salvador, it's all dark: pitch black, even though it's barely 7 p.m. here. I figured we would be chasing the sun. There is no daylight savings time in Central America. My sense of logic and order has all faded in its place.

When we flew home from El Salvador towards Houston last summer, our first trip to the country, we could see the mega prison. From the plane window, the Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo (CECOT) was unmissable, really—stark, fluorescent, conspicuous. The prison was self-consciously terrifying; it caught me off guard, like you weren't supposed to be able to see a place like that.

Flying to San Salvador in March from Miami, the crowd was different than last year’s: a lot of spring breakers. The landscape is inky dark. I can see stars from the plane. I can see the occasional town. More strings of light as we approach San Salvador.

The El Salvador International Airport is forty-five years old. Sparkling and glittering and new when conceived in 1980 mid-civil war between the U.S.-backed, military-dominated government of El Salvador and multiple left-wing guerrilla groups, its opening preempting the promise of a surf town that never came to be. El Salvador remained fraught with turmoil and gang violence even after the 1992 Chapultepec Peace Accords that ended the war. Welcome To Surf City: El Salvador, the sign before customs says in a faded blue and white font.

Those familiar with El Salvador used to say not to arrive at night here. Even two years ago, they told my boyfriend David not to arrive at night, but we were reassured that now, it’s safe. "It's visibly better every time we come here," David’s colleagues told me at the Palestra Society Conference last summer. The new president is doing a good job. Infrastructure. Safety. We arrive in pitch black. Customs goes quickly. We pass photographed portraits of President Nayib Bukele and the First Lady hung above a chair resembling a throne, where tourists can sit and pose for a photo opportunity assembled for a photo opportunity, and then an outdoor food court reminiscent of a midwestern mall: Papa John’s, Pizza Hut, some teenagers selling soda. We Americans are right at home.

Nayib Bukele was elected president of El Salvador in 2019, running under his own new party, Nuevas Ideas, championing a populist investment in El Salvador’s economic and cultural development. Born to a wealthy Salvadoran family of Palestinian ancestry, he quickly gained popularity and notoriety for his iron-fist policies, seeking safety, law, order in a nation that had long been riddled first by war, and then by gang violence. He was elected again in 2024 with a whopping 84.7% of the vote after he autrocouped the constitutional judges in judiciary court and replaced them entirely with pro-Bukele judges—then revised the constitution to allow for consecutive terms. Tough on crime, and the self proclaimed “ coolest dictator in the world” and “Philosopher-King” in his oft-changing X-bio, Bukele has transformed El Salvador from the Murder Capital of the World to the Safest Country In The Western Hemisphere, bringing homicide rates from over 100 per 100,000 in 2015 to around 1.9 per 100,000 in 2024. Now 1.6% of El Salvador’s population of 6.4 million is currently in prison. And in keeping with the young president’s verve, prioritizing innovation, social media, and cultural capital, El Salvador became the first country in the world to adopt Bitcoin as legal tender in September 2021.

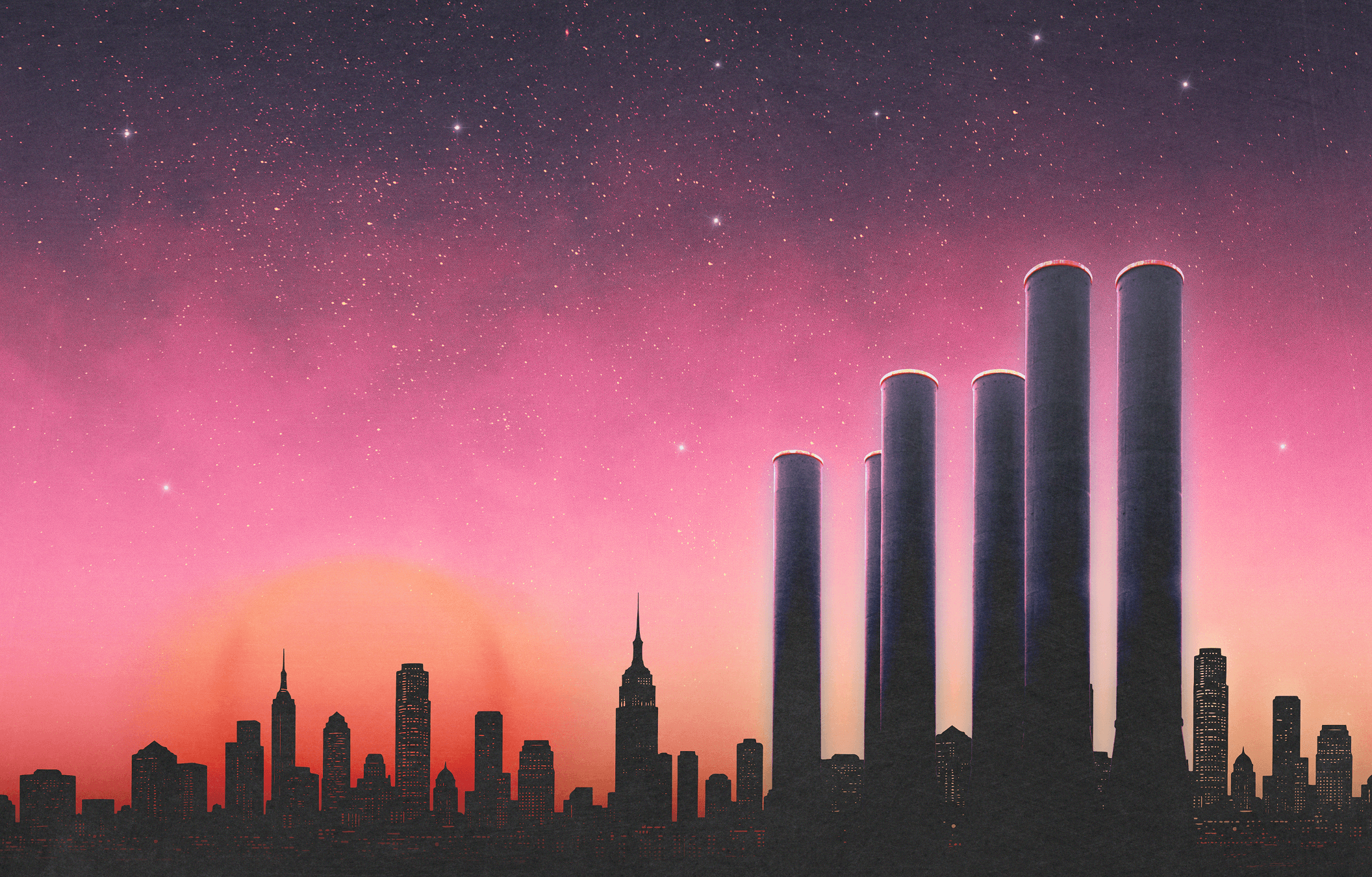

A rapidly transforming pro-autocracy pro-Bitcoin nation had begun to pique the interest of some foreigners abroad. In certain spheres of cryptocurrency, tech, and esoteric right-leaning internet communities, El Salvador had begun to be imagined as a new frontier.

The goals of Palestra Society were still somewhat obfuscated to me, but seemed to tow the lines between imperialism, philanthropy, and an almost spiritual faith in Bitcoin. The Palestra Conference we’d arrived for seemed to represent a meeting of a certain type of mind. On Palestra Society’s X page, AI-generated images of Greco-Roman architecture, stone sculpture, flowing water, ancient weapons, and sculpted bodies crafted an aesthetic vision that towed the line between futurism and tradition. “‘Uncounted ruins, cloaked by dense growth, await excavation.’ Yucatán, 1969,” one post read. The conference attendees seemed to view the new El Salvador as both impressive and malleable. Disappointed with how modernity had panned out by-in-large, many of them had sought refuge online. Now, they were seeking this, but perhaps something more; influence, escape, autonomy, here.

A tall man carrying an iPhone-sized vape picks us up at the airport. I know Sitrym from New York: he is one of David’s colleagues. A somewhat nomadic biohacker loosely based in Austin, Sitrym would serve as our guide and host for the trip this time.. "Sitrym assures me that it's a good thing we're running late," David tells me, hoping to stop for a beer of his own. “Sitrym has been at the food court, drinking."

***

The Palestra Society had first been introduced to me at a party in New York in August 2024 as a “neoclassical gym” in El Salvador. “Do you want to go?” David had asked me. “Go where?” I had asked. “El Salvador,” David had responded,

David, a computer programmer working in cryptocurrency, had been advised to attend the upcoming Palestra Society Conference by an acquaintance at the New York party. We had received other strange invitations like this before. The year prior, we had been invited to a charter city called Prospera on the island of Roatán, Honduras that operated with economic, legal and regulatory autonomy as a Zone for Employment and Economic Development. (Recently, Prospera has run up against significant legal tension with the government of Honduras). In New York, there were often Praxis parties thrown in downtown bars or lofts; celebrating a still hypothetical and ephemeral city-state with plans for construction in the Mediterranean as the world's first “Internet-Native-Nation.” Many of my boyfriend's colleagues were nomadic, the target audience for this sort of initiative, shuffling from Patagonia to Austin to New York to Costa Rica to here, locating friends and community in social groups largely formed online, and seeking to exit from modern frameworks of society they felt were folding in or failing around them. Though my position in this world had some characteristics of “insider”—girlfriend, writer, plus one, this did not often translate to clarity on the nature of these trips when I attended. Boys club, work trip, cult. I would arrive knowing almost no one. However, there would be a free place to stay.

My research in August had revealed only what Palestra Society has to say about itself: which was to say, not much. “Palestra Society is a private research organization centered on the principles of natural law and sovereignty,” I wrote on my laptop, in Manhattan. “Membership online advertises subcategories of Community and Content for $499 a year,” I note. “Palestra Society is a futurist movement built on ancient principles.” A 2024 video produced by Palestra from a previous Palestra Society conference titled Age of Light: Dr. Jack Kruse depicted a group of men in white linen, standing mostly barefoot on a foggy hillside in front of a black screen and a glowing circular image, which looked something like a cross between a planet, a wave, an alien, and an eye. Dr Jack Kruse was introducing a draft of a new medical “law” for El Salvador, which would include legal protection against mandatory medical interventions, state regulation of “electromagnetic field exposure,” and the establishment of “light spectrum standards for health.” Jack Kruse, a neuroscientist and now-influencer had gained popularity and notoriety online as either genius or snake-oil-salesman. He had made his exodus from Florida to El Salvador in 2022, seeking freedom from medical research restrictions, and healing from the sun.

In practice, the premise of Palestra seemed to be a kind of new frontier society for foreign castaways (mostly male; mostly working remotely in tech) in an up-and-coming nation where the dollar went far, and Bitcoin was king. In this idealized Palestra, the Bukele regime would both welcome the arrival of wealthy tech-forward foreigners, and share in their visions for an autocratic red-tape-free future. But in the interim, “Palestra” seemed to hover somewhere between a retreat, think tank, and aesthetic vision of the future. It was unclear to me which of these visions was more real.

When I first met David, I had noticed that many of his colleagues hoped to live forever. “Will you indoctrinate me into a cult?” I asked him, soon after we met. “I’m a programmer,” David told me, our unspoken understanding being that the culty sides of these industries involved ideas and topics he chose to largely ignore.

Closing my computer after my initial scouting of Palestra, we flew to El Salvador the following morning for our first trip to the utopia-in-progress.

***

The first time I visited Palestra for a week was in August 2024. The trip was centered around Palestra’s annual conference. We had convened at the airport with a group of men in linen shorts, and then made our way to the sprawling Palestra mansion, an art deco style compound built into the hills of Escalón, one of San Salvador’s wealthiest neighborhoods. At the mansion, we were greeted by a college-aged young man who introduced himself as Palestra founder Michael McClusky’s assistant. The terrace had been blanketed with Red LED Light for the conference. Dr. Jack Kruse, who Palestra had promoted, had been a guest of honor. His bio displayed on the Palestra website read Exiled Neurosurgeon: Health is about Light NOT Food. The crowd was eclectic, if culturally predictable: we met the founder of a new magazine (that was mostly about Tennessee) and a sculptor who told us how he had been cancelled for making art about “force and form.” However, the only evidence of cancellation I was able to find online were the sculptor’s own comments lamenting the whole sordid affair. Better to be cancelled, I guess, than unknown.

I had left Palestra in August still unsure about the premise of the place. Health center or cultural exodus. City or Airbnb. So when David was invited back in March 2025, to spend the week coding with some colleagues, I decided to accompany him again.

Arriving again in March 2025, most of the guests from the annual conference have gone home or moved onto other temporary living situations. However, the red light remained, and became a permanent fixture of the house, even as the mansion itself has drifted into a ghost town of sorts, sparsely populated by a few unrelated characters who vaguely aligned themselves with the Palestra “vibe” — drawn to the sun, vaguely right-wing online sentiments, utopic aesthetics of water and light and and ancient architecture. The emptiness of the place now dispels any illusion of Palestra as a growing town in its own right at least in its current state.

While Palestra seemed desolate, things in El Salvador proper were different. Sitrym, driving us from the airport at 80 miles per hour, explained how “the traffic has gone from bad to worse with more cars on the road,” Though, there are not too many cars as far as I can see—we’re out late and, heading into the city, we’re driving against traffic, “Why are there more cars on the road?” I ask Sitrym. Sitrym shrugs. “More prosperity,” he says. People feel safer.

As we drive up towards San Benito, where wealth rises visibly with altitude, Sitrym is talking about the highway project, where Bukele is trying to expand the number of lanes, bury phone lines, and boost capacity for business and tourism traffic along the coastline. He's talking about the passport initiatives for foreign artists and philosophers, which offers Salvadoran citizenship to foreign investors “highly skilled individuals” in exchange for financial contribution. Sitrym is talking about the changes being made and the things that still must be done to make El Salvador a better country. “You want to go upstream and fix a lot of the things that are causing air and water pollution,” he says. “Infrastructure is fixable, but it requires a wholesale change in the relationship between state and society, and state and the land that they run."

"I imagine they just want to import a new class of rich people from elsewhere," event manager Matt is saying.

"Eh, not really, " Sitrym says. “They're trying to bring in people who can solve big problems."

There is a sense of synchronicity between Sitrym’s stated goals for Palestra and the interests of El Salvador that surprises me, in contrast to the isolationist spirit of the charter city. He would like to improve the nation’s education, stop deforestation, establish permaculture—to optimize the country rather than to wrest away control of it. The interests seem parallelly libertarian and autocratic—the myth of a place where one can do whatever one wants, under the reign of an enlightened leader. Here, the Bitcoin pioneers found themselves already aligned—here, they’d be working with what they viewed as a budding utopia, rather than confront the bureaucratic red tape and subsequent challenges of building an imagined paradise of one's own within a sovereign nation.

The conversation turns to the topic of “un-schooling”—a model of education derived from John Holt’s notion of harnessing children’s natural curiosity for learning, rooted in play and practical work. In El Salvador, grade school is only in session for a half-day. Some affiliates of Palestra have been working with a town north of Surf City to launch an Un-School campus to teach the kids drone technology, history, ecology.

I lay my head on the luggage in the backseat, and I ask Sitrym if I should talk to a SeaSteading expert for my story. The movement, which envisions online communities of like-minded people expanding into autonomous physical territories, has been a hot topic in tech circles these days. The creation and habitation of autonomous territories abroad were particularly appealing for those who viewed Bitcoin as salvation and the regulations that typically accompany citizenship to a sovereign nation as a roadblock to their research. Sitrym takes a sharp turn on the road, and addresses my question about the Seasteader of interest. “You’re talking about Patri Friedman,” he says.

“Patri Friedman,” I note. Milton Friedman’s grandson. Moving away from seasteading in favor of strong, capitalist, sovereign leaders, like in El Salvador.

“I went to his post-eclipse party and everyone but me and one guy did ‘circling’,” Sitrym is saying. “It’s hypnosis, basically.”

***

We take a few sharp turns into the hills of the wealthy Escalon neighborhood and the foliage is more muted in the darkness but the headlights still illuminate the road’s steep bends, mansion walls traced with compound-like gates, mostly-abandoned guard outposts, palm groves, a roundabout. This mansion, the Palestra House, would look like a compound, if it weren't all so open air.

I drag my bag inside. I notice tall orange stucco walls and a garage door that could seal the whole place off, but the house residents aren’t closing it these days, preferring to maintain a spirit of openness. I walk through interior thick wooden doors and then see high ceilings, eight bedrooms, a stone wall fountain, and an expanse of terrace built into the hillside. The infinity pool seems to stretch over all of San Salvador, the population density mapped out by pockets of speckled light. Darker in the distance. All hazy over the volcanoes.

The last time I was here, someone had taken the necessary steps to mark Palestra House on Google Maps, but this landmark status disappeared by the time I returned. So too, has the Palestra Banner in the garage, most of the Lindy Juice (Palestra branded fresh-squeezed orange juice) in the fridge, the packs of Zyn and the Mastic Gum of Gods (tough chewing gum designed to chisel one’s jawline) and the groups of young men on the terrace hitting Geek Bars in bermuda shorts, linen, sunglasses.

I decamp to the room where we’ll be staying, which is described to me as “the gym.” Eating t cashews while the guys cook steak outside under dim red light, I take stock of bed, a dresser, a single cinder block weight machine, and one elliptical, and put to rest the theory of Palestra as an ancient revival style fitness community.

Sitting on the floor, I transcribe the recording of a call with Palestra’s co-founder, Michael McClusky, from a few weeks back. Clusk, as he liked to be called, had left his job as a Stripe programmer f in 2022, moving to El Salvador, and founding Palestra with another man who remained anonymous and who is no longer involved. The project had been part fresh squeezed orange juice company, part social club, and part effort to gain influence and assimilation within the Salvadoran government. Recently, Clusk had been working with the El Salvador Ministry of Culture on archeological initiatives, using laser scanning technology to map archaeological sites and cultural heritage previously hidden beneath dense vegetation.

“Palestra is a place that is connected to nature, and that is also a model for the type of place we want to see in the world,” Clusk is saying in my headphones. “Palestra is a research center for most of the year, and a place to meet now and then.” He continues: “Palestra is mostly an art project for now.”

***

Time for dinner. Steak, obviously. David is manning the grill, and the fire is dangerously flaring. A skinny long haired programmer is complaining that the cleaning ladies keep throwing out his cup of cigarette butts. Sitrym is telling me about the Randonautica app—you use your mind to set an intention, and the app then gives you coordinates for where to go. The conversation is confusing. “They are looking for a platonic city that does not exist,” I note.

Hot humid air. It’s too hot for steak. A small cluster of programmers and Bitcoiners are seated around the table. “Has there been any heat lightning?” I ask one of the men. He looks at me blankly. “Heat lightning isn't real.”

David pours me a glass of rum, and then one more. I am eyeing the swelling fire on the grill suspiciously and he is telling me to be less neurotic. David pours me one more glass of rum. “Do you know what we call this?” Sitrym asks me. “What?” I responded. “Unschooling!”

Last August’s conference had been framed as an investigation into “The State As a Work Of Art” — a reference to the work of Jacob Burckhardt, Renaissance historian and intellectual forefather of Nietzsche.

“Good morning, San Salvador,” Curtis Yarvin had opened his lecture last summer. “I am so happy to be here in the only monarchy in the Western Hemisphere.”

The premise of our trip to El Salvador being cryptocurrency, Yarvin’s attendance — monarchist philosopher, father of neoreaction, father of Urbit — had initially surprised me, but the tone of the lectures had quickly revealed themselves as dealing more in culture, idealism, thought experiments, and even zealotry, than in anything suggesting real pragmatism.

The conference had been held at Teatro Nacional last summer, a stately historical building constructed in 1911 in the city center. The Palestra House — technically the home of a wealthy Salvadoran family leased on an incremental basis — had been the social hub. I had spent my evenings on the terrace, half eavesdropping. I overheard young men talking about the automobile, the impact of speed, “seeking speed, road technology, and red light therapy. “I just don’t see the average man as something to hold up, spiritually,” the cancelled sculptor I’d spoken with earlier had said, confidently. Last summer, they had been talking about a plan to stimulate the arts in El Salvador by providing studio space and economic incentives for artists who had left the country during El Salvador’s most violent days and then returned. There was a real philanthropic tone to much of the conversation, somewhat in contrast to most of the attendees' dual libertarian instincts and fondness for autocracy.

“Is Palestra going to be a charter city?” I interjected into one conversation last summer. A college-aged boy in a baseball cap wrinkled his nose. “The problem with a government granting autonomy immune to regime change is that when the regime changes, the new regime just overthrows the regime change law,” he said. I nodded, hesitant to ask about long-term considerations if the current El Salvador regime were to change. Sensing my confusion, the young man clarified: “the Salvadoran government is pro-business, so the upside of an autonomous zone is low.”

As a plus one, I was able to drift around the house mostly uninterrupted. One morning, while I sipped branded Lindy Juice at dinner and drank beer on a terrace above a bar, sweltering heat, a tall guy in a baseball hat introduced himself to David. “Are you based?” he asked. David hesitated. Before he could respond, the man turned to me. “Do you know what that means?” he asked. “Do you know what that means?”

***

In my next visit to Palestra in August, I spent my mornings in traffic, in taxis, headed towards downtown San Salvador. “Downtown was hot gang territory right up until the state of exception,” my ride-share companions told me. “There are visible infrastructure transformations every few months,” according to a Bitcoiner standing on the balcony of the Teatro at the conference. There were No Smoking signs on the first morning, but they were gone by the next. Cigarettes were constant here. The biohacking impulse was one towards true immortality, but these health-obsessed chain smokers were seeking loopholes.

“People ask, ‘why don’t you just make a more based version of postmodernism?’,” the cancelled sculptor said, during his presentation. “Why would you stand in quicksand? We need to exit.”

At the conference lunch break, I grabbed a Lindy Juice and stepped outside to walk the city center with a group of other stragglers: Matt from New York and Curtis Yarvin’s young assistant. The city center had been hot and bustling. We’d walked past the National Library of El Salvador—modern, glass, built with aid from China as a “monument of friendship” between the two countries recently erected in November 2023 . We’d circled the National Palace. Stumbled upon advertisements featuring women breastfeeding. “Look at these pro-natalist posters,” Matt beamed. Back at the Teatro, Yarvin’s assistant pointed me towards a barefoot and shirtless middle-aged man whom I recognized as the ‘Bitcoin Doctor’ I’d been told would be attending. “That’s Jack Kruse,” he said. “He has like seven malpractice lawsuits against him in the state of Louisiana. That’s what you could talk about if you wanted to write a hit piece.” I responded: “I don’t want to write a hit piece.”

Kruse himself was emerging as the hot topic of the conference. The utopian slant of the whole thing extended beyond, evidently, ideas of political, social, and cultural alignment and was becoming, instead, an opportunity for Salvation in a more biblical sense. In the Sun and the Heat and the Safest Country In The Western Hemisphere, you could leave behind bureaucracy, taxes, and social control to pursue research, freedom, and utopic visions uninhibitedA later panelist displayed photographs of an old wooden door knob alongside a modern metal creation. Dismissing the metal iteration, he told us that we could leave behind anything ugly, here, too. Bathed in red light and veins pumping with methylene blue, you could leave behind illness. The focus of Palestra was not explicitly on biohacking to the degree of a place like Prospera, an alternative crypto city-state, but I got the sense that many of the attendees were also hoping to cheat death itself. In contrast to the disembodied or ephemeral nature I had previously understood many notions of techno-futurism to take on, the ethos of Palestra Society was strikingly grounded in body and place. Artificial intelligence might threaten to make the human form obsolete, but the bio-hacking-forward-Bitcoiners wanted to immortalize it, make it stronger, and keep it safe forever. In contrast to most new city states, with their relentless emphasis on “building,” the Palestra apostles seemed to view El Salvador as a pre-existing Eden of a kind. There existed a perfect world, right here, heaven on earth, and they had just been smart enough to find it and move. Escape to Utopia, rather than create it.

On stage, later, Kruse, still barefoot, his lecture not yet begun, was talking to an audience member about what would become of the children of the Salvadoran gang members who had all been locked up.

“Make El Salvador Great Again,” Kruse ruminated, once his talk began. “We are the misfits. El Salvador is a nation of misfits.”

About the Author

Chloe Pingeon is a writer based in New York