tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

Civilization

•

Nov 13, 2025

California's City on a Hill

On 70,000 acres in the Bay Area, an ambitious plan for a new city takes shape. Is California Forever the antidote to American stagnation?

Free email newsletter:

Get Arena Magazine in your inbox.

In 1959, the Army Corps of Engineers released a report, Future Development of the San Francisco Bay Area 1960-2020. The report, a hundred-or-so bound pages, was “designed to show, on a decade-to-decade basis, how the San Francisco Bay Area could grow.” The Future Development report predicted that, by 2020, the San Francisco Bay Area would have a population of 14.4 million—almost double the current population of 7.7 million. The report also predicted that manufacturing employment in the region would triple, with 24% of the population expected to work in manufacturing. But today, only 353,000 (or 4.6% of Bay Area residents) work in manufacturing. In the last 65 years, a lot went wrong.

But the Army Corps of Engineers did get one thing right. They “correctly predicted that sometime around 2020 someone would want to build a city here,” Jan Sramek, the founder of California Forever, a company trying to build a manufacturing focused city in the Bay Area, told me.

“Here” means Solano County. We are in a small office park in Fairfield, California, an hour drive from San Francisco. The California Forever office is unassuming; neighboring a few medspas, financial offices, and a dental surgeon. Although Sramek is originally from Czechia, he has lived in California for a bit more than a decade; he came in 2014 to, like many others, seek the California start-up dream.

As we walked out of the office, about to drive through California Forever’s land, which is more than double the size of San Francisco (at around 69,000 acres), Sramek handed me one of his forty copies of the Army Corps of Engineers report in a worn-down red box. “I was so concerned that someone was going to figure out what we were doing during the land assembly but I systematically bought every single one of these that I could find online.” While buying up the land around Solano County, he systematically collected the reports that explain how a new city may take shape so that others wouldn’t steal his idea or worse, thwart it.

When I asked him where he shipped the reports to, he laughed. “I shipped them to PO boxes that I maintain all over America. And then I had them rerouted to the same place, and then I had them stored in a storage facility somewhere in Napa.”

Julia Blystone, California Forever’s Head of Communications, pointed to Sramek, 6’7” and wearing an all-American outfit of a tucked-in blue button-down and jeans: “Someone who comes from Eastern Europe.”

Born behind the Iron Curtain in Czechia in Dřevohostice, “a village of 1400 people in the middle of nowhere,” Sramek was two-years-old when the Berlin Wall fell. Born to a car mechanic turned small business owner, Hollywood saturated his childhood: spreading American—really Californian—stories of the “the profoundly optimistic” nineties around the world. On the early internet, he found a full scholarship to Bootham School, a quaker boarding school in York, England, and stayed in the United Kingdom both for college and his first post-grad job at Goldman Sachs. “It's a lot easier to explain building a city to my grandma, who used to work in a steel mill, than to explain to her what I used to do at Goldman Sachs,” Sramek told me.

Sramek first drove through Solano County on a fishing trip in early 2016. He recalled chatting with his fishing guide, who lived locally, about the fisherman's wife, who worked in Mountain View—an 80-minute commute in the morning, two hours on the way home. “I said, ‘How does that work? You have a two-year-old child?’ And he said, ‘well, she gets up at 3 a.m. in the morning to beat the traffic, and then she comes home early before the afternoon traffic, and then I go really late.’ I was like, ‘So when do you see each other?’ And he says, ‘well, only on the weekends.’ And I'm like, that's completely batshit insane.”

The California Forever plan is to build a new city for 400,000 people, including a shipyard at the confluence of the Sacramento River and the Bay and a foundry—to restore the Golden State’s industrial capacity. When he first followed his now-wife Naytri to California, Sramek was underwhelmed by California’s promise of growth and prosperity after moving to San Francisco in 2014 because housing was in such short supply: “I was surprised, confused, disappointed by the fact that we couldn't build anything. And I thought it was profoundly sad.” Speaking of his frustrations with California’s reluctance—or inability—to build more housing, Sramek said: "If you tried to design a system that was going to completely break up society, make everyone fight and make everyone hate each other, you would design the California Land Use system."

Once he became a California resident, Sramek experienced a common Californian coming-of-age: coming to the realization that while California excels at capitalism and attracting elite human capital—in particular, through start-ups and Hollywood—it was failing miserably at governance. California law makes it difficult to build multi-family housing and forces builders to navigate an unwieldy discretionary review process, hence why the fisherman’s wife was driving nearly four hours to-and-from work. What was worse is that California’s policies, Sramek argues, essentially force its successes to move out-of-state. “We dream up the future in San Francisco, design it in Silicon Valley, and then you need somewhere to build it. But right now, the build part happens in Texas and Florida, and I think that that's really bad for our ability to innovate.” He repeated several times that it’s a three-day trip for an engineer to visit the Texas or Ohio factory he is building from California—a trip that could be shortened down to an eighty-minute drive from Silicon Valley to Solano County. The economic growth that California creates is offshored to other states.

Sramek told me that he tried to convince himself that his idea to build a new city in Solano County was crazy—or, as he’d say it, “batshit insane.” He wrote down seventy-five reasons why the plan would fail. “Maybe there's some rare ecosystem there. Maybe there isn't enough water. Maybe you can't build enough transportation infrastructure. Maybe the politics doesn't make sense. Maybe the soil isn't suitable for building, and it's really expensive to build there.” But after seven months of testing each objection, Sramek told me “I couldn't find the fatal flaw.” To Sramek, the story of the fisherman’s wife was a “market-slash-planning inefficiency”—regulations stymied growth, so the market could not properly react by building more housing in the needed locations. In a ploy to solve this inefficiency, Sramek, over a series of eight years, raised a billion dollars and used that money to buy up land in Solano County. He currently employs fifteen full-time employees, as well as around eighty political, planning, and engineering consultants who work close to full-time trying to bring California Forever into existence.

On a late October afternoon, I went to meet Sramek on the land that will, if all goes right, become California Forever. After we meet in the Fairfield office, we drive for a bit more than two hours through the dirt roads of what will, if Sramek’s moonshot becomes a reality, become California Forever. We drive by Travis Air Force base and then subdivisions surrounded with palm trees, out of place in the prairie of Solano County. We drove by two small hamlets, Collinsville and Bird’s Landing, each of which consisted of a half-abandoned settlement with a half-a-dozen houses. “This is called Collinsville because it was started by Collins. That's called Bird’s Landing, not because birds landed there, but because it was started by a guy called Bird.”

In other words, California is composed of hundreds of cities and towns, all founded by someone. But Collinsville, purchased by C.J. Collins in 1859, and Bird’s Landing, settled by John Bird in 1865, now have a shot of becoming (at least part of) a “real city”: they are now owned by California Forever. For now, the two towns sit as a physical record of the risks of trying to start a new city. But the two towns were not started with a billion dollars of venture capital funding.

I am a fourth-generation Angeleno. Anywhere else in the world, those roots would be laughably shallow, short of one hundred years. But in California-time, my ancestors came long ago. Los Angeles was only founded in 1781, by the Spanish Empire in their drive to settle the New World. And San Francisco was only founded five years earlier, in 1776.

California is dotted with cities—not major ones, but cities nevertheless—that were founded extremely recently. A striking number are also run privately. Disneyland was initially run by Disneyland, Inc., the corporation formed to finance, build, and govern the park. Irvine is run by The Irvine Company, an owner and developer of master-planned communities across Southern California. Foster City, which was founded by T. Jack Foster, real estate mogul and former mayor of Norman, Oklahoma, in the early 1960s (the first houses sold for less than $20,000, perhaps because this Bay Area suburb was built atop an engineered landfill). Then there is also Beverly Hills (founded in 1906 by the Rodeo Land & Water Co), Carmel-by-the-Sea (founded in 1902 by the Carmel Development Company), Mission Viejo (developed beginning in 1963 by the Mission Viejo Company), Westlake Village (Daniel Ludwig, incorporated in 1981), and Weed (Abner Weed, founded in 1904). There was no better place for a private individual to build his own utopia than in California.

Beyond California, Sramek spoke about the successes of Summerlin, Nevada, a master-planned commercial and residential area to the west of Las Vegas; the Woodlands, Texas, a metro area spanning two counties and host to the corporate campuses of Occidental Petroleum Corporation and Halliburton; Reston, Virginia, a D.C. suburb influenced by the 1960s Garden City movement with open space and forests aplenty; and Columbia, Maryland, which is halfway between D.C. and Baltimore, and the second most populous community in Maryland behind Baltimore itself. Master-planned cities are as American as Apple Pie: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Savannah, Georgia were both colonial-era planned grids centered around public space, planned in 1682 and 1733, respectively. Our capital, Washington, D.C., was even master-planned by French-American artist Pierre Charles L’Enfant, who was appointed by George Washington to build the “federal city” intentionally in a style fit for the new nation.

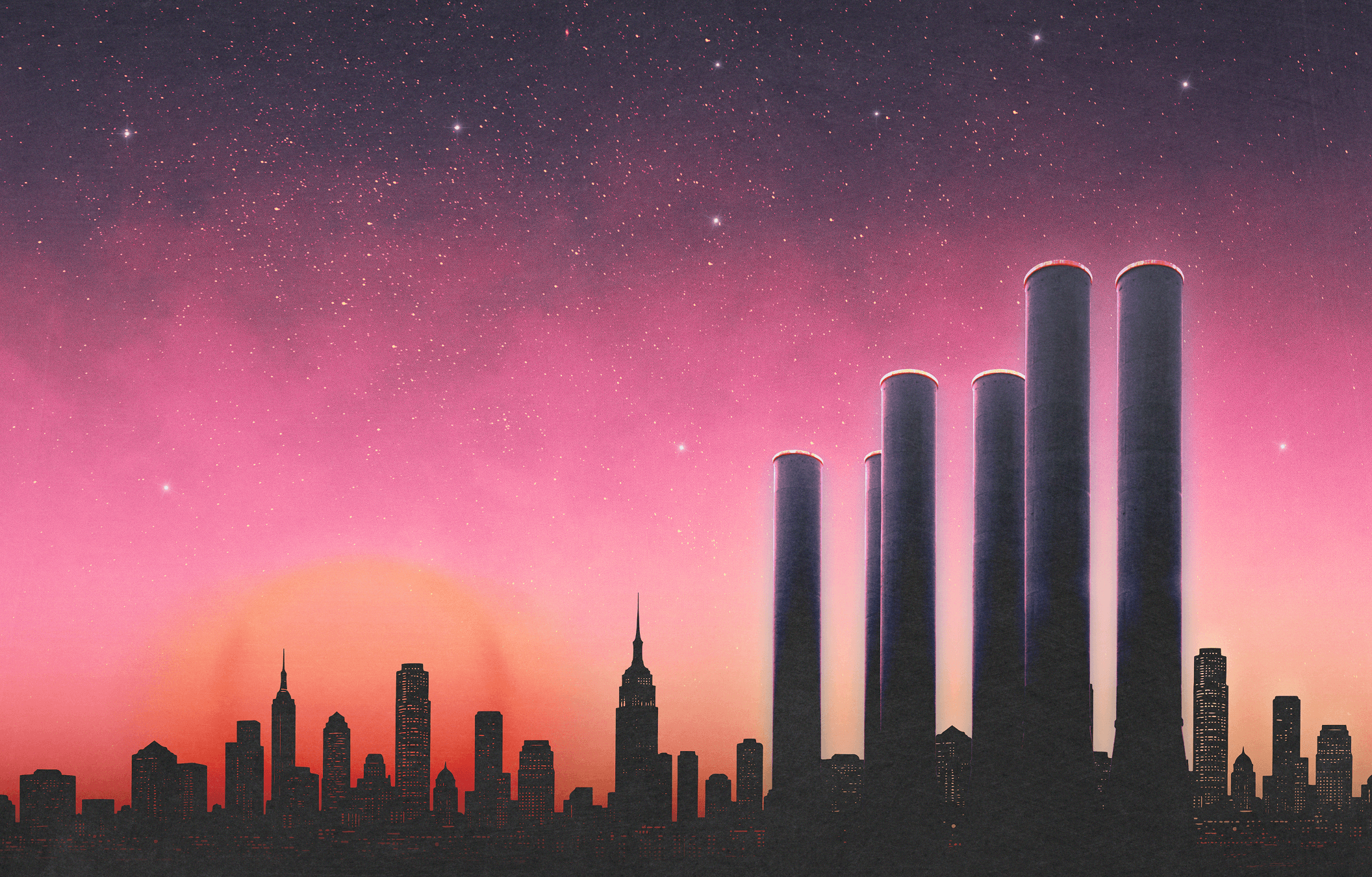

But, all of the sudden, starting in the mid-sixties, America stopped building new cities. Not developments (there are still plenty of those), but great cities, centers of industry and culture. Not because our population is shrinking; quite the opposite. From 1960 to 2020, the U.S. population grew from 179,323,175 to 331,449,281, with 92% of that growth occurring in urban centers. But almost all of that urban population growth has occurred because existing cities have grown, not because new ones have been built. California mirrors these national trends: there has been exponential population growth in existing cities, creating the crushing housing crisis the state is now known for, but no new cities have emerged to pick up the slack. Once Los Angeles and San Francisco became American, capitalist expansion naturally drove the growth of both: with Hollywood accelerating population growth from 102,000 to around 1,238,048 in Los Angeles from 1900 to 1930, and back-to-back gold rushes (in gold and tech, respectively) in San Francisco drove the population first from around 1,000 (1848) to 25,000 (December 1849) to 56,802 (1860) and second from 723,959 (1990) to 873,965 (2020). But while driving into a sea of 1100 windmills (“there’s enough steel and concrete and rebar in the ground to build fifteen Empire State Buildings just from the windmills”), Sramek laments about how, if he did not decide California Forever, the land that could become a Great American city would become an ocean of modest developments scattered among prairie grass.

“I think it's profoundly sad that we are taking this incredibly optimistic story of California and letting it stagnate at best,” Sramek said. The slow, unambitious development of California currently looks like “suburban sprawl,” Sramek says, where developers plan to build two hundred homes and a small office park, with the vague promise to “bring jobs.” But office parks are not “a credible plan to bring jobs” to the suburbs or exurbs because they are not providing any new industries or companies that could create jobs. In a better world, California housing developers could have been heroes for building homes in a place millions more people desperately want to live; instead, the current default outcome of a new development is stale sprawl and hell-bent inertia. Sramek blames the false promise of “200 houses and an office park” for the vilification of developers in general, who have become associated with a dreary, endless suburbia. He gestured to a line of stucco-house subdivisions as we cruised on the two-lane highway. The view reminded me of home.

For much of the history of Silicon Valley, the San Francisco Bay Area was the perfect geographical complement to the technological frontier created within its bounds. The Bay Area of the sixties was populated by residents who fit (at least) one of two tropes: hippies or engineers. The sixties hippie counterculture, which encouraged freedom and experimentation with communal living and psychedelic drug use, was geographically proximate to the hard-nosed engineers who were building the first modern computers. On paper, the two groups should not have gotten along, but because of this shared optimism and geographic proximity, the two elements of futurism—wide-eyed social experimentation and cutting-edge science—fused together across cultural barriers to become techno-utopianism, which would come to define “Silicon Valley” culture by the century’s end. Back then, all Californians were (in one way or another) utopians.

That was the California that Sramek, sitting in Dřevohostice, Czechia, saw as a child in the nineties: when he would eagerly sit down to American media, which was continuing to portray the idealized West Coast counterculture of the 1960s. And this was the California Sramek was expecting to find when he finally made it to the Bay Area in 2014. But by the time Sramek made his way West, technoutopianism was in short supply—people were throwing rocks at Google buses, and homelessness became rampant, as more and more of the world’s problems were being blamed on the omnipresent outputs of “Big Tech”. And what optimism was left was purely reserved to the digital world, with the still-alive promise of cryptocurrencies and artificial intelligence. Desperate to escape the crushing regulations and environment in California, Silicon Valley libertarians (who still harbored dreams of a better physical-world state) threw their support behind seasteading, an optimistic and escapist project to establish autonomous above-water settlements—called “seasteads”—in international waters.In 2008, PayPal cofounder Peter Thiel gave $500,000 in seed capital to Patri Friedman (Milton’s grandson) and Wayne Gramlich’s Seasteading Institute; conveniently, in international waters, the U.S. government would have no jurisdiction to impose restraints (or collect taxes). However, no such seasteads have been built.

Silicon Valley elites, doubling down on ambition, have since backed numerous new efforts to create new, privately developed cities—but always in far away places, selling the dream of a clean slate away from whatever had gone wrong in California. There’s Praxis, a proposed digital-first city-state of 10,000 that has raised over $525 million in financing and has, for the last few years, been attempting to purchase land in the Mediterranean. Then there is Prospera, a charter city in Honduras that was set on becoming a hypercapitalist technoutopia, but is now suing the Honduran government for $11 billion after its ‘special autonomous zone’ (ZEDE) status was flouted. Culdesac, a $140 million development in Tempe, AZ, broke ground on the first purpose-built walkable neighborhood in 2019, but it only houses 1000 residents and a mere 21 local businesses. In 2022, Balaji Srinivasan, former CTO of Coinbase and a venture capitalist, wrote a book entitled The Network State, pitching digital-first highly aligned communities that have the capacity for collective action. The book and “network state” meme was wildly popular in tech circles during the COVID-19 pandemic, but no such states have been created. The closest might be Esmeralda: a small, walkable town which is in the process of buying land ninety minutes north of San Francisco to create a new walkable and intellectually dynamic town in wine country, with a focus on family and community for commuters to San Francisco (rather than trying to create a new stand-alone industry town). And for the real eccentrics, the frontier is no longer on Earth, but on Mars.

But a small but committed group of Silicon Valley investors, who still are interested in making the future look like the future, are now looking closer to home for a solution to Silicon Valley’s woes.

“I specifically found people who wanted to double down on California and make a huge bet on the state in something that was really risky, very illiquid, very long term,” Sramek told me. His investors include LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, philanthropist Laurene Powell Jobs, Stripe co-founders Patrick and John Collison, former GitHub CEO Nat Friedman, Sequoia chairman Michael Moritz, and the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz. Many of California Forever’s investors have been (predictably) attacked for trying to hijack a small town to turn it into a billionaire’s paradise with no regulations, or locals. Sramek dismissed the attacks offhand. “We can either fund [a new city] from wealthy families who are very committed to California, and who can afford to take a forty year view, or I can go to some private equity firm and a bank, take out a seven year loan and a seven year line of financing” and create another boring subdivision (like the ones that already sit half-filled all over California). “Which one do you think is going to allow us to build a better place?”

California, with the longest continental coastline on the Pacific, was once at the bleeding edge of the frontier: In his 1893 essay "The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” historian of the American West Frederick Jackson Turner argued that the American national character is uniquely dependent on the frontier, because it forced self-reliance, a rugged independence, and the constant bucking away of old norms in pursuit of progress and expansion. By backing California Forever, some of the Valley’s most intelligent investors are betting that California can once again behave like a frontier. Today, the “frontier” is less physical than intellectual: it has been recast as technological advancement or even multiplanetary expansion. But California Forever is a bet that land that was settled hundreds of years ago can still provide the much-needed physical infrastructure for the intellectual exploits that will define the future. It's betting that the next frontier lies on the same ground as the old frontier.

And yet, for all the high minded theorizing, California Forever still lacks the frontier’s autonomy: the city needs to win popular support in Solano County to begin building. To get permission, Sramek’s team will need to convince residents of Solano County to approve development. When Sramek began buying up the land for his dream city in 2017—first with an “irresponsible” loan, then with more and more financial backing—he was met with suspicion. Local residents and national security observers expressed fears that a foreign adversary was buying up the land. Sramek, who did not want to announce California Forever until he had secured the land (lest opponents of the project move to stop it), would tell curious family and friends that his project was “a group of American investors who are buying the land for as a very long term investment, and we're not going to comment on who they are, and we're not going to comment on what are we going to do with the land.”

The night before we had met, Sramek had dinner with a cattle rancher who he had purchased land from at four times the market price. It was a “win-win-win situation” (Sramek has been buying the land in Solano County at up to four times the market price on average). Sramek is quite confident that the California Forever project, is on net, hugely net beneficial for the residents of Solano County. He told me that through buying the land, “we minted 700 millionaires and everyone was very happy.” The vast majority of the people who had sold land to Sramek were pleased with the outcome.

However, a few who regretted the transactions became a vocal minority. And in 2023, after California Forever came forward about its acquisition of more than 50,000 acres of land, the public outrage started. The narrative went as follows: wealthy out-of-towners (worse yet: developers) were trying to turn an authentic rural community into an exclave of the elitist Bay Area. On the website California ForNever, several Solano County residents had the following testimony to give: “This is a money making opportunity for the “developers” with a long list of over the top promises”; “This misconceived fever dream of these audacious and arrogant billionaires will cause a myriad of unintended consequences”; “Solano County services are already stretched thin.”

After my trip to Solano County, I found the Facebook page of the same name as the website: “California ForNever - A group opposing California Forever/Flannery” (Flannery, Inc. is the name of the legal entity behind California Forever, named after the street where Sramek purchased his first parcel of land). The page has, as of writing, 3,250 members and an average of four posts a day, and features similar content to that found on the website.

Common complaints include: concerns about the meager water supply, California Forever’s potential encroachment on the Travis Air Force Base (Sramek told me that its employees face a housing shortage and so will certainly benefit from new housing nearby), possible traffic jams on the county’s two-lane highways, and the general “feeling” that out-of-towners are taking over a small rural community. Ironically, the Solano County residents are using Facebook (a primary export of Silicon Valley in the early aughts) to voice their concerns about Silicon Valley overreach.

In November 2024, a ballot measure asking Solano County residents whether they approved development of the “East Solano Plan” ( as it was called then) was approved for a vote.But California Forever pulled the ballot measure after polling showed that 70% of Solano County residents opposed the proposal—a certain loss for the new city. On October 14, 2025, California Forever returned with a new 250-page plan: the nearby Suisun City (the county’s smallest city, with a population of a mere 30,000) would annex 22,873 acres of land. Rather than relying on voters directly, California Forever now only has to win the favor of elected officials and administrators. For the Suisun City annexation to commence, the plan first needs to be approved by the Suisun City Council and the Solano County LAFCO (Local Agency Formation Commission). After both approvals are secured, California Forever will “only” be blocked by a litany of state agency permits. Suisun City will publish a draft Environmental Impact Report in early 2026, which Sramek estimates will be around 12,000 pages; the final version of the report will be used by Suisun City when evaluating whether to approve the annexation.

When I visited the California Forever office, the power of the government to stifle the California Forever project was the elephant in the room. The entrenched power of the regulatory state was not in the spirit of the optimistic decor of the office, which featured maps and plans strewn across the table in the central room, as well as bookshelves featuring a litany of books about great American cities and urban planning: Detroit: The Dream is Now, Cities Under Siege, Walt Disney Imagineering, Edge City: Life on the New Frontier, as well as (I counted them) eighteen copies of Abundance by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson. And this was the abridged version of Sramek’s collection: Sramek described how his interest in building a new city has turned into “this obsession when I went on this deep dive of reading 500 books about urban planning and architecture and real estate development and cities and infrastructure and history of California and land use reform and CEQA [The California Environmental Quality Act] and history of all of the major cities in the world.” He also mentioned that, when he moved to the U.S. in 2013, he went on a seven-week “reading binge” of biographies of the founding fathers. Hamilton’s biography stuck out (Sramek told me that seeing the musical “was one of the most singular defining artistic experiences” of his life) .

But real-life government is a lot less glamorous than Broadway made it out to be. When I asked Sramek if he was worried about the 2026 California gubernatorial election—of a new governor who may have the authority to stamp out the California Forever promise forever, or at least the for well-foreseeable future—he shrugged. “The vast majority of Californians don't want to be the state that we have been for the last 10 years,” he insisted.

While the initial ballot measure did not end in California Forever’s favor, “it was a useful way to get out all the concerns that everyone had, have the big debate” about the future of Solano County. Sramek continued: “And the reality is, the conclusion of that debate was the two cities invited us to come in and talk about annexation.”

Californians are progressives; they wear their openness to change like a badge of honor. And “you can’t call yourself a progressive if there’s no progress. You can't call yourself progressive if half of your friends' kids—and now your kids, probably—are living in Tennessee and Texas,” as Sramek told me. In 2020, for the first time in California’s history, California’s population decreased, and the state lost seats in the House of Representatives. It can’t go on like this.

The United States has built exactly zero cities from scratch in the 21st century. By contrast, China has built a few dozen new cities in the same twenty-five years. (The biggest “new” American cities of this century are just incorporations of previously-populated suburbs like Centennial, CO and Sandy Springs, GA—so jurisdictions, not cities.) Of course, many of these new Chinese cities sit empty, created for the sake of national prestige and to give its unemployed workers jobs digging holes. But Sramek thinks that a progress-oriented electorate, tired of watching California fail, may take a step towards closing the gulf with China.

When I asked Sramek about the perception that California Forever is undemocratic, Sramek clarified that the project’s success “will require approvals by many, many, many elected officials.” If California Forever succeeds, it will be a project by the people, for the people, of California. The only question that remains is whether the people, in fact, want something new.

At the end of our drive around the California Forever land, we arrive at an abandoned brick midcentury modern house on a hill. Purchased in the sixties by a descendant of a California steel fortune and used to entertain their friends, the house was abandoned in the eighties. It has a view of the Suisun Bay, where Sramek planned his shipyard.

One thing me and Sramek never talked about on our journey is the name of his new city, California Forever. If all goes according to plan, California Forever will be ten times the size of Suisun City, but it will legally share the name. When I asked Sramek if California Forever would, going forward, be known as Suisun City, he acknowledged that yes, California Forever will be a part of Suisun City. But “often in real estate development, particularly if you have a large master plan, the master plan gets a name as well, and so we'll see exactly how that happens. That's still a couple of years down the road.” There is a sense of grandeur in building a new city, one well-captured by the necessarily impossible promise of forever. Under the new plan, the name may change, but the spirit of California Forever will live on.

Sarcastically describing the California ForNever crowd, Sramek said: “We've been building cities for 10,000 years, and somehow, after doing it for 10,000 years, we've now arrived at the perfect exact number of cities.” Californian optimism, the kind the state was known for fifty years ago, would instruct us that San Francisco and Los Angeles will last another 10,000 years (so functionally “forever” compared to a human lifetime), a beacon of optimism at the Western edge of the Western world. California Forever, as an American-borne expression of this Californian Optimism, has the chance to join the pantheon of great cities, with plenty of spoils to go around.

But Californian pessimism, the kind the state is known for now, would lead to the opposite conclusion: that San Francisco and Los Angeles, if not destroyed by climate change, or deportations, or drug use, or crime, will be relics at best. These cities were founded just short of 250 years ago; the state’s collective unconscious feels unsure if they can last 250 more. If our existing cities are barely going to last the next century, then what is the use of building more?

California Forever is a promise to overcome the ultimate test of a declining society—both a bet that we can build a new city, and a bet that this new city can be built in the same location as our present stagnation. Sramek believes that without the ambition of great projects like California Forever, the future will, by default, look like a nothing more degraded version of the present. “If you wiped off the physical infrastructure of America, but you kept all of the people here, and all of the IP here, and then we had to go and rebuild the country, we couldn't do it in 500 years. There's no way! You would have famines. You would have people living in huts made from animal skins and sitting by bonfires. In order to continue our civilization, it is insufficient to theorize about building civilizations; we have to actually try to rebuild civilization. He continues, “We are unable to rebuild the civilization that we live in today, which I think is a radicalizing thought.” In order to continue to grow Western civilization, it has to be possible to build new cities to save civilization. Sramek is an optimist because someone must be.

About the Author

Julia Steinberg is General Manager of Books and an editor at Arena. She can be found on X at: @juliasteinberg.