tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

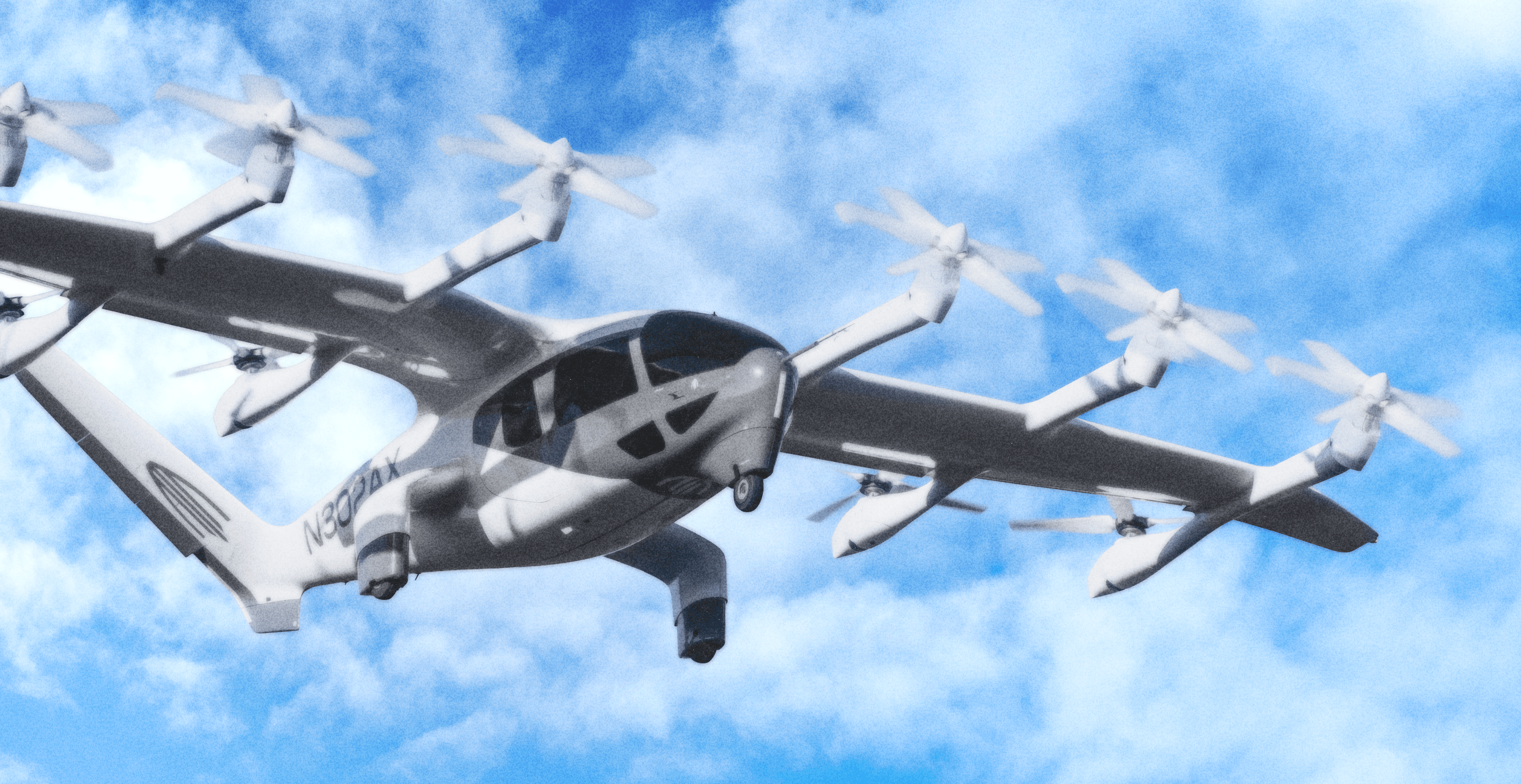

Civilization

•

Sep 10, 2025

A Return to Form

Dreaming of Liberty and Titanium

Sign in to keep reading

Sign up for free to see the rest of the article.

About the Author

Zaitoon Zafar is a junior editor at Arena Magazine. She can be found on X at: @zaitoonx.

ComponentTest