tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

tt

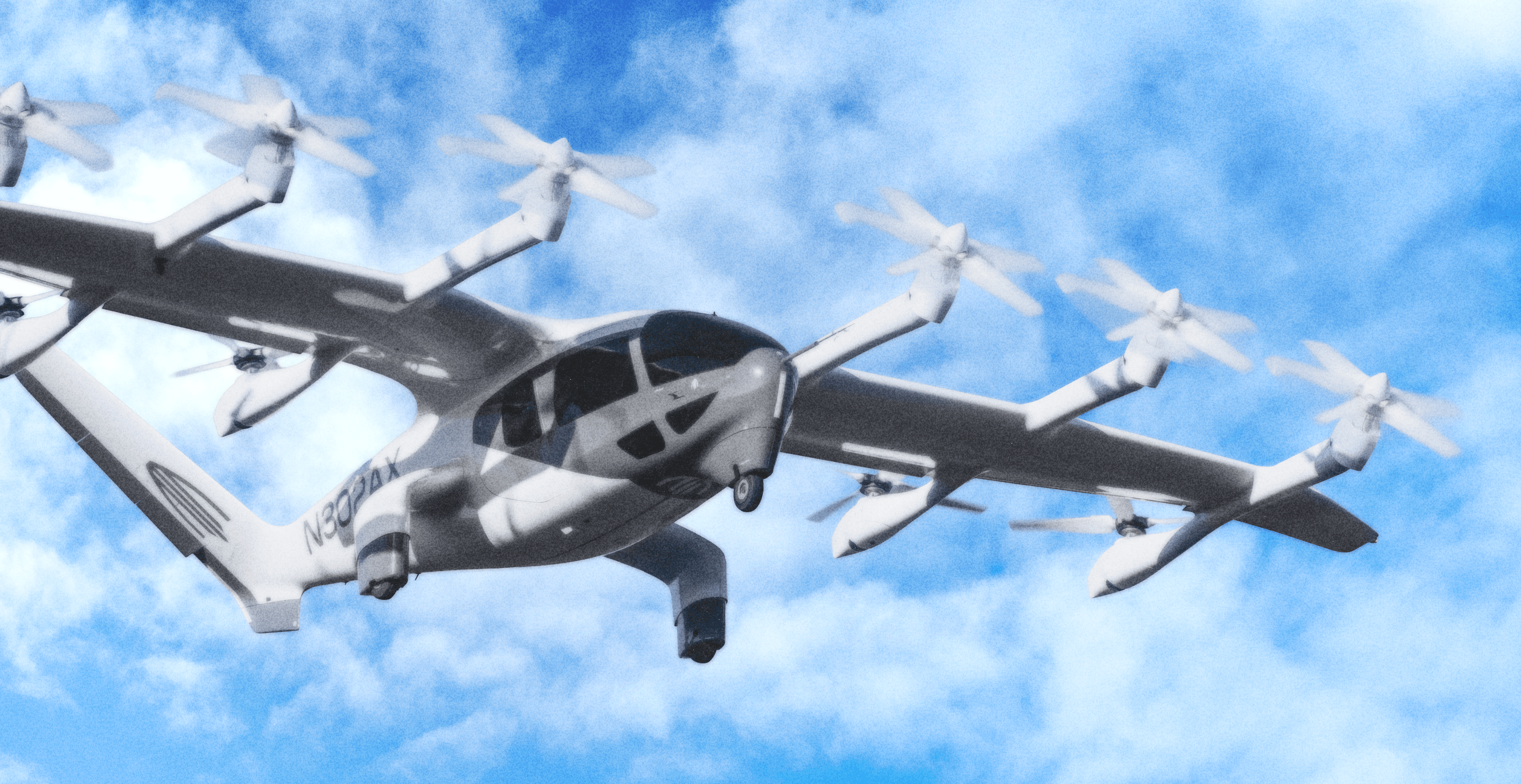

Technology

•

Sep 17, 2025

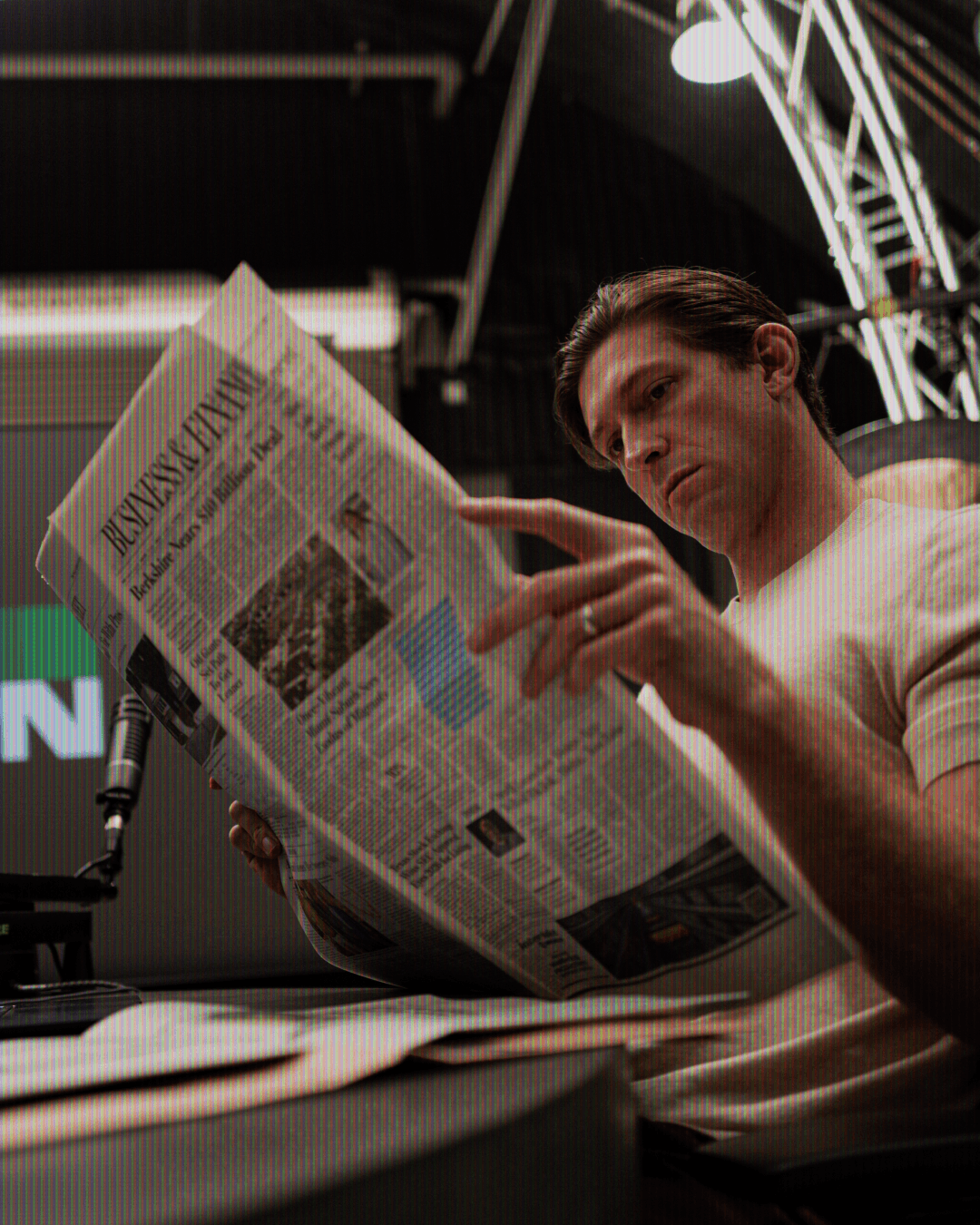

Ryan’s World

Flexport CEO Ryan Petersen on the craziest year for global trade.

Sign in to keep reading

Sign up for free to see the rest of the article.

About the Author

Maxwell Meyer is the founder and Editor of Arena Magazine, and President of the Intergalactic Media Corporation of America. He graduated from Stanford University with a degree in geophysics. He can be found on X at: @mualphaxi.

ComponentTest